Indonesia produced 420,000 metric tons of coffee in 2007. Of this total, 271,000 tons were exported and 148,000 tons were consumed domestically. Of the exports, 25% are Coffea arabica and the balance is Coffea canephora. [1] In general, Indonesia’s Arabica coffees have low acidity and strong body, which makes them ideal for blending with higher acidity coffees from Central America and East Africa.

1 History

2 Cultivation

3 Sumatra, Mandheling, Lintong and Gayo

4 Sulawesi, Toraja, Kalosi, Mamasa and Gowa

5 Java

6 Bali

7 Flores

8 Papua

9 Harvesting and processing

10 Coffee research

11 Coffee Associations

12 See also

13 Notes

14 External links

15 Further reading

History

The Dutch governor in Malabar (India) sent a Yemeni or Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica) seedling to the Dutch governor of Batavia (now Jakarta) in 1696. The first seedlings failed due to flooding in Batavia. A second shipments of seedlings was sent in 1699. The plants grew, and in 1711 the first exports were sent from Java to Europe by the Dutch East India Company, known by its Dutch initials VOC (Verininging Oogst-Indies Company which was established in 1602. Within 10 years, exports rose to 60 tons per year. Indonesia was the first place, outside of Arabia and Ethiopia, where coffee was widely cultivated. VOC monopolized coffee trading in 1725 to 1780.

The coffee was shipped to Europe from the port of Batavia (now Jakarta). There has been a port at the mouth of Ciliwung River since 397 AD, when King Purnawarman established the city he called Sunda Kelapa. Today, in the Kota area of Jakarta, one can find echoes of the sea-going legacy that built the city. Sail driven ships still load cargo in the old port. The Bahari museum occupies a former warehouse of the VOC, which was used to store spices and coffee. Menara Syahbandar (or Lookout Tower) was built in 1839 to replace the flag pole that stood at the head of wharves, where the VOC ships docked to load their cargos.[2]

In the 1700s, coffee shipped from Batavia sold for 3 Guilders per kilogram in Amsterdam. Since annual incomes in Holland in the 1700s were between 200 to 400 Guilders, this was equivalent of several hundred dollars per kilogram today. By the end of the 18th century, the price had dropped to 0.6 Guilders per kilogram and coffee drinking spread from the elite to the general population.[3]

The coffee trade was very profitable for the VOC, but less so for the Indonesian farmers who were forced to grow it by the colonial government. In theory, production of export crops was meant to provide cash for Javanese villagers to pay their taxes. This was in Dutch known as the Cultuurstelsel (Cultivation system), and it covered spices and a wide range of other tropical cash crops. Cultuur stelsel was iniated on coffee at Preanger region of West Java. In practice however, the prices set for the cash crops by the government were too low and they diverted labor from rice production, causing great hardship for farmers.

By mid of 1970’s the Ducth East Indies expanded Arabica coffee growing areas in Sumatra, Bali, Sulawesi and Timor. In Sulawesi the coffee was first planted in 1750. In North Sumatra highlands coffee was first grown near Lake Toba in 1888, followed in Gayo highland (Aceh) near Lake Laut Tawar in 1924.

In 1860, a Dutch colonial official, Eduard Douwes Dekker, wrote a book called “Max Havelaar and the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company”, which exposed the oppression of villagers by corrupt and greedy officials. This book helped to change Dutch public opinion about the “Cultivation System” and colonialism in general. More recently, the name Max Havelaar was adopted by one of the first fair trade organizations.[3]

In the late eighteen hundreds, Dutch colonialists established large coffee plantations on the Ijen Plateau in eastern Java. In the 1920’s smallholders throughout Indonesia began to grow coffee as a cash crop. However, disaster struck in the 1876, when the coffee rust disease swept through Indonesia, wiping out most of Typica cultivar. Robusta coffee (C. canephor var. robusta) was introduced to East Java in 1900 as a substitute, especially at lower altitudes, where the rust was particularly devastating.

The plantations on Java were nationalized at independence and revitalized with new varieties of Coffea arabica in the 1950s. These varieties were also adopted by smallholders through the government and various development programs.

Cultivation

Today, more than 90% of Indonesia’s coffee is grown by smallholders on farms averaging one hectare or less. Much of the production is organic and 19 farmers’ cooperatives and exporters are internationally certified to market organic coffee. There are more than 20 varieties of Coffea arabica being grown commercially in Indonesia. They fall into six main categories:

Typica – this is the original cultivar introduced by the Dutch. Much of the Typica was lost in the late 1880s, when Coffee Leaf Rust swept through Indonesia. However, both the Bergandal and Sidikalang varieties of Typica can still be found in Sumatra, especially at higher altitudes.

Hibrido de Timor (HDT) – This variety, which is also called “Tim Tim”, is a natural cross between Arabica and Robusta. It was first collected in East Timor in 1978 and planted in Aceh in 1979.

Linie S – This is a group of varieties was originally developed in India, from the Bourbon cultivar. The most common are S-288 and S-795, which are found in Lintong, Aceh, Flores and other areas.

Ethiopian lines - These include Rambung and Abyssinia, which were brought to Java in 1928. Since then, they have been brought to Aceh as well. Another group of Ethiopian varieties found in Sumatra are called “USDA”, after an American project that brought them to Indonesia in the 1950s.

Caturra cultivars: Caturra is a mutation of Bourbon coffee, which originated in Brazil.

Catimor lines – This cross between Arabica and Robusta has a reputation for poor flavor. However, there are numerous types of Catimor, including one that farmers have named “Ateng-Jaluk”. On-going research in Aceh has revealed locally adapted Catimor varieties with excellent cup characteristics.

Sumatra, Mandheling, Lintong and Gayo

Coffee from this western-most island in Indonesia is intriguing and complex, due to the large number of small-holder producers and the unique “Giling Basah” (wet hulling) processing technique they use. At the green bean stage, coffee from this area has a distinctive bluish color, which is attributed to processing method and lack of iron in the soil.

Coffees from Sumatra are known for smooth, sweet body that is balanced and intense. Depending on the region, or blend of regions, the flavors of the land and processing can be very pronounced. Notes of cocoa, tobacco, smoke, earth and cedar wood can show well in the cup. Occasionally, Sumatran coffees can show greater acidity, which balances the body. This acidity takes on tropical fruit notes and sometimes an impression of grapefruit or lime.

Mandheling is a trade name, used for Arabica coffee from northern Sumatra. It was derived from the name of the Mandailing people, who produce coffee in the Tapanuli region of Sumatra. Mandheling coffee comes from Northern Sumatra, as well as Aceh. Lintong

Lintong coffee is grown in the District of Lintongnihuta, to the south-west of Lake Toba. This large lake is one of the deepest in the world, at 505 meters. The coffee production area is a high plateau, known for its diversity of tree fern species. This area produces 15,000 to 18,000 tons of Arabica per year. A neighboring region, called Sidikilang, also produces Arabica coffee.

Gayo Mountain coffee is grown on the hillsides surrounding the town of Takegon and Lake Tawar, at the northern tip of Sumatra, in the region of Aceh. The altitude in the production area averages between 1,110 and 1,300 meters. The coffee is grown by small-holders, under shade trees.

Coffee from this region is generally processed at farm-level, using traditional wet methods. Due to the Giling Basha processing, Gayo Mountain coffee is described as higher toned and lighter bodied than Lintong and Mandheling coffees from further east in Sumatra.

Sulawesi, Toraja, Kalosi, Mamasa and Gowa

The Indonesian island of Sulawesi, formerly called the Celebes, lies to the north of Flores. The primary region for high altitude Arabica production is a mountainous area called Tana Toraja, at the central highlands of South Sulawesi. To the south of Toraja is the region of Enrekang. The capital of this region is Kalosi, which is a well known brand of specialty coffee. The regions of Mamasa (to the west of Toraja) and Gowa (to the south of Kalosi), also produce Arabica, although they are less well known.

Unlike many of Indonesia’s islands, Sulawesi is geologically ancient, dating back more than 100 million years. This long history has resulted in soils with a high iron content – thought to affect coffee flavor.

Sulawesi coffees are clean and sound in the cup. They generally display nutty or warm spice notes, like cinnamon or cardamom. Hints of black pepper are sometimes found. Their sweetness, as with most Indonesian coffees, is closely related to the body of the coffee. The aftertaste coats the palate on the finish and is smooth and soft.

Most of Sulawesi’s coffee is grown by small-holders, with about 5% coming from seven larger estates. The people of Tana Toraja build distinctively shaped houses and maintain ancient and complex rituals related to death and the afterlife. This respect for tradition is also found in way that small-holders process their coffee. Sulawesi farmers use a unique process called “Giling Basah” (wet hulling).

Java

Java’s Arabica coffee production is centered on the Ijen Plateau, at the eastern end of Java, at an altitude of more than 1,400 meters. The coffee is primarily grown on large estates that were built by the Dutch in the 18th century. The five largest estates are Blawan (also spelled Belawan or Blauan), Jampit (or Djampit), Pancoer (or Pancur), Kayumas and Tugosari, and they cover more than 4,000 hectares.

These estates transport ripe cherries quickly to their mills after harvest. The pulp is then fermented and washed off, using the wet process, with rigorous quality control. This results in coffee with good, heavy body and a sweet overall impression. They are sometimes rustic in their flavor profiles, but display a lasting finish. At their best, they are smooth and supple and sometimes have a subtle herbaceous note in the aftertaste.

This coffee is prized as one component in the traditional “Mocca Java” blend, which pairs coffee from Yemen and Java. Some estates age a portion of their coffee for up to three years. As they age, the beans turn from green to light brown, and the flavor gains strength while losing acidity. These aged coffees are called Old Government, Old Brown or Old Java.

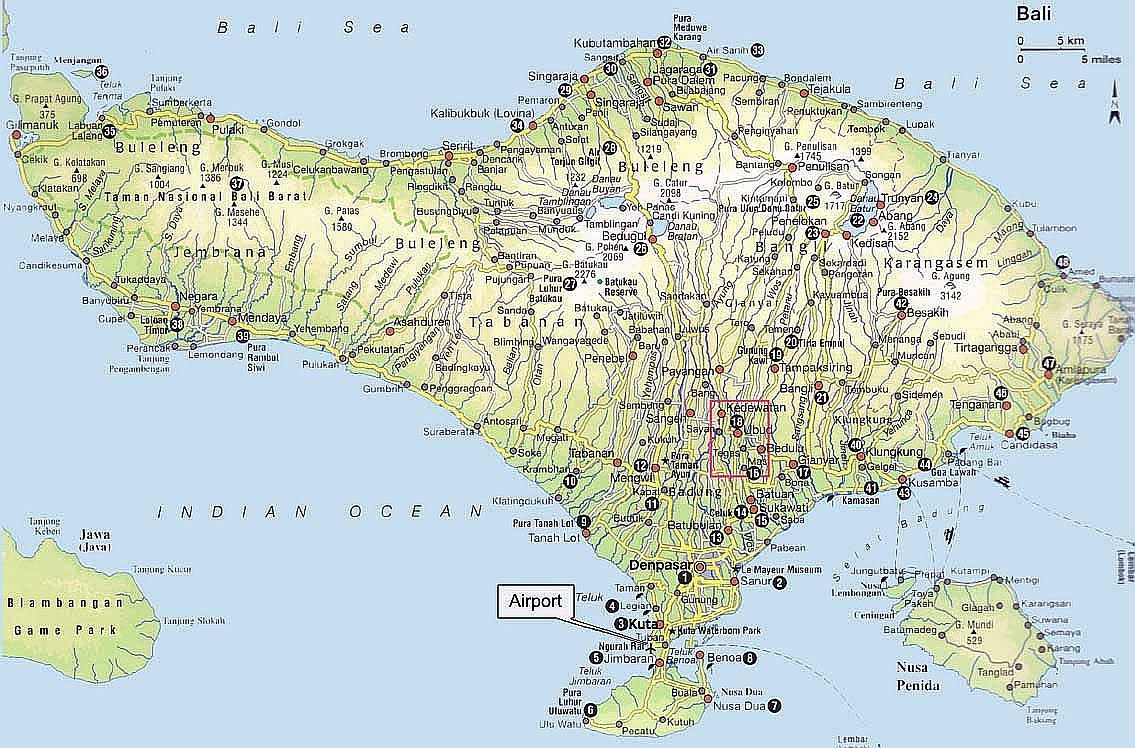

Bali

The highland plateau of Kintamani, between the volcanoes of Batukaru and Agung, is the main coffee growing area. Many coffee farmers on Bali are members of a traditional farming system called Subak Abian, which is based on the Hindu philosophy of "Tri Hita Karana”. According to this philosophy, the three causes of happiness are good relations with God, other people and the environment. The Subak Abian system is ideally suited to the production of fair trade and organic coffee production.

Stakeholders in Bali, including the Subak Abian, have created Indonesia's first Geographic Indication (G.I.). Once it is recognized by the government, this G.I. will protect Kinatamani coffee from blending or mis-labeling.

Generally, Balinese coffee is carefully processed under tight control, using the wet method. This results in a sweet, soft coffee with good consistency. Typical flavors include lemon and other citrus notes.

Flores

Flores (or Flower) Island is 360 miles long, and is located 200 miles to the east of Bali. The terrain of Flores is rugged, with numerous active and inactive volcanoes. Ash from these volcanoes has created especially fertile Andosols, ideal for organic coffee production. Arabica coffee is grown at 1,200 to 1,800 meters on hillsides and plateaus. Most of the production is grown under shade trees and wet processed at farm level. Coffee from Flores is known for sweet chocolate, floral and woody notes.

Papua

New Guinea is the second largest island in the world. The western half of New Guinea is part of Indonesia. The Indonesian half of the island was formerly called “Irian Jaya”. Today, it is known as Papua, and it is divided into two provinces – Papua and West Papua.

There are two main coffee growing areas in Papua. The first is the Baliem Valley, in the central highlands of the Jayawijaya region, surrounding the town of Wamena. The second is the Kamu Valley in the Nabire Region, at the eastern edge of the central highlands, surrounding the town of Moanemani. Both areas lie at altitudes between 1,400 and 2000 meters, creating ideal conditions for Arabica production.

Together, these areas currently produce about 230 tons of coffee per year. This is set to rise, as new companies are setting up buying and processing operations. These companies are assisting farmers to obtain organic and fair trade certification, which will significantly improve incomes. The area is extremely remote, with most coffee growing areas inaccessible by road and nearly untouched by the modern world.

All coffee is shade grown, under Kaliandara, Erytrhina and Abizia trees. Farmers in Papua use a wet hulled process. Chemical fertilizer pesticide and herbicide are unknown in this origin, which makes this coffee both rare and valuable.

Harvesting and processing

All Arabica coffee in Indonesia is picked by hand, whether it is grown by small-holders or on medium-sized estates. After harvest, the coffee is processed in a variety of ways, each imparting its own flavors and aromas to the final product.

A small number of farmers in Sulawesi, Flores and Bali use the most traditional method of all, dry processing. The coffee cherries are dried in the sun, and then dehulled in a dry state.

Most farmers on Sulawesi, Sumatra, Flores, and Papua use a unique process, called “Giling Basah” (or Wet Hulling). In this technique, farmers remove the outer skin from the cherries mechanically, using rustic pulping machines, called “luwak”. The coffee beans, still coated with mucilage, are then stored for up to a day. Following this waiting period, the mucilage is washed off and the coffee is partially dried for sale.

Collectors and processors then hull the coffee in a semi-wet state, which gives the beans a distinctive bluish-green appearance. This process reduces acidity and increases body, resulting in the classic Indonesian cup profile.

Larger processing mills, estates and some farmer’s cooperatives on Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi and Bali produce “fully washed” coffee.

The most unusual form of coffee processing in Indonesia is “Kopi Luwak”. This coffee is processed by the Asian Palm Civet (Paradoxurus hermaphoditus). The animals eat ripe coffee cherries and their digestive process removes the outer layers of the fruit. The remaining coffee beans are collected and washed. Coffee experts believe that the unique flavor of Kopi Luwak comes, at least in part, from the extraction of natually occuring potassium salts from the beans during the digestive process. This results in a smooth, mild cup, with a sweet aftertaste. Kopi Luwak is very rare, and can retail for moer than $600 per kilogram.

Coffee research

The Indonesian Coffee and Cocoa Research Institute (ICCRI) is located in Jember, Java. Current activities of ICCRI in the coffee sector include:

Land mapping to identify new areas for coffee production

Research on coffee diseases and identification of resistant planting material

Farmer training on improved production and processing techniques

Supply of coffee seedlings for improved varieties

Supply of coffee processing and testing equipment

The Agribusiness Market and Support Activity (AMARTA) is conducting research on the effectiveness of the Brocap Trap technology in Toraja, Sidikilang and Gayo. This trap is designed to catch the Coffee Cherry Borer (CCB) insect, a major pest in coffee. It was developed by CIRAD, a French agricultural research institute. Brocap traps have been extensively adopted by coffee farmers in Central America

Coffee Associations

Indonesia’s coffee industry is represented by two associations. The Association of Indonesian Coffee Exporters (AICE), also known by its Indonesian acronym “AEKI”, is composed of Arabica and Robusta coffee exporters. AICE was founded in 1979 and it issues compulsory export licenses for coffee.

The Specialty Coffee Association of Indonesia (SCAI) formed in 2008. SCAI members focus exclusively on the production, export and marketing of Indoensia’s Arabica coffees. This includes farmers’ cooperatives with 8,050 members, exporters, roasters, importers and coffee retailers in the Arabic coffee industry.

skip to main

|

skip to left sidebar

skip to right sidebar

Black as the devil, Hot as hell, Pure as an angel, Sweet as love.

Travel to Indonesia

Contact Our Team:

Raja Kelana Adventures Indonesia

Raja Kelana Adventures Indonesia

Email: putrantos2022@gmail.com

Facebook Messenger: https://www.facebook.com/putranto.sangkoyo

Our Partner

Blog Archive

-

▼

2008

(29)

-

▼

September

(24)

- COFFEE

- Kopi Gayo

- Marissa's Story

- Clearing The Java Confusion

- Pentingnya Perlindungan Indikasi Geografis atas Pr...

- COFFEE IN INDONESIA

- Bali - Coffee Plantations

- Map of Indonesia

- Coffee in Indonesia

- Next hot commodity? Arabica coffee beans

- Famous Coffee Quotes

- Coffee - Illustrated

- Difference: Arabica vs. Robusta

- KOPI - Komoditi Unggulan

- Potensi Daerah Bangli - Kopi Arabika

- Banyuatis Coffee Manufacturing in Buleleng

- Kintamani Coffee - not Export Quality

- Bali Coffee - Export Opportunity

- Eco Friendly Balinese Coffe

- Arabica vs Robusta: No Contest

- How to Make A Good Coffee

- Bali Arabica

- Robusta vs. Arabica

- Bali - Robusta or Arabica ?

-

▼

September

(24)