Celebrating A Gift From Bali: Delicious Confusion

Original Article

October 8, 2010

Celebrating A Gift From Bali: Delicious Confusion

By MATTHEW GUREWITSCH

NO longer quite the inaccessible Shangri-La of antique travelogue, Bali remains, for artists of all kinds and seekers of a spiritual bent, an isle of pristine enchantments. To musicians with or without the cosmic baggage, the fascination lies in the intricately layered pulse and shimmer of the gamelan, the indigenous form of orchestral ensemble, dominated by percussion and associated for centuries with Balinese ritual and devotion.

Since the 1980s the clarinetist and composer Evan Ziporyn has made the pilgrimage often. His new opera, “A House in Bali,” celebrates his forerunner Colin McPhee, a Canadian-born composer and scholar best remembered by fellow acolytes of Bali’s musical heritage. Happening on a few scratchy phonograph records from Bali in 1929, McPhee found his calling. If not for him, the traditions that flourish today might be extinct.

The opera is based mainly on McPhee’s memoirs of the same title, published in 1946 to a rave review in The New York Times by the anthropologist Margaret Mead, who had known McPhee in Bali. “This book,” Mead wrote, “is not only for those who would turn for a few hours from the jangle of modern life to a world where the wheeling pigeons wear bells on their feet and bamboo whistles on the tail feathers, but also for all those who need reassurance that man may again create a world made gracious and habitable by the arts.”

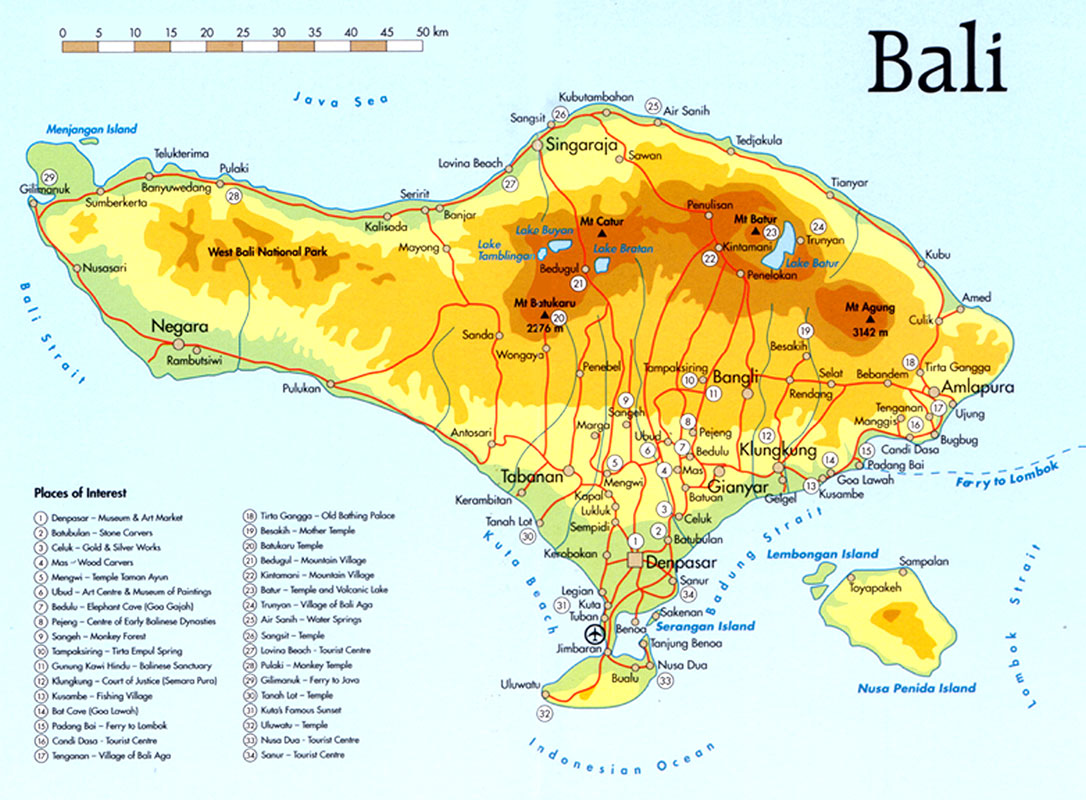

For logistical and sentimental reasons Mr. Ziporyn’s opera received its first, unstaged, preview in June 2009 on the steps of a temple in Ubud, a Balinese arts mecca, surrounded by spreading rice terraces and plunging ravines. The stage premiere followed three months later in Berkeley, Calif. This fall the opera reaches the East Coast, with performances in Boston and in the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival Thursday through Saturday.

The scoring is for a balanced ensemble of Western (the Bang on a Can All-Stars, of which Mr. Ziporyn is a founding member) and performers from Bali whose contributions are equal but for long stretches separate. On Oct. 30 a program of Mr. Ziporyn’s compositions in the Making Music series at Zankel Hall will include further examples of Western-Eastern fusion.

Born in Montreal in 1900, McPhee was hardly the first Western composer to thrill to the gamelan. The former Wagnerian Claude Debussy was transfixed by Balinese musicians at the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1889. The cosmopolitan Maurice Ravel was likewise taken. But it was left to McPhee to sail halfway around the globe to experience the music in its home.

For much of the 1930s he made Bali his home, studying, redeeming historic instruments from pawnbrokers, recruiting children to learn and play. He left in 1938, never to return, but worked on his magnum opus, “Music in Bali,” for the rest of his life. He had barely finished correcting the page proofs in the medical center of the University of California, Los Angeles, when he died, in 1964.

In his memoir McPhee’s evocations of gamelan music are bewitchingly specific.

“At first, as I listened from the house,” one passage begins, “the music was simply a delicious confusion, a strangely sensuous and quite unfathomable art, mysteriously aerial, aeolian, filled with joy and radiance. Each night as the music started up, I experienced the same sensation of freedom and indescribable freshness. There was none of the perfume and sultriness of so much music in the East, for there is nothing purer than the bright, clean sound of metal, cool and ringing and dissolving in the air. Nor was it personal and romantic, in the manner of our own effusive music, but rather, sound broken up into beautiful patterns.”

McPhee went on to analyze the music’s layered architecture: the “slow and chantlike” bass, the “fluid, free” melody in the middle register, the “incessant, shimmering arabesques” high in the treble, which ring, in McPhee’s phrase, “as though beaten out on a thousand little anvils.” Add to all this the punctuation of gongs in many registers, the cat’s-paws and throbbings and thunderclaps of the drums, the tiny crash of doll-size cymbals and the “final glitter” of elfin bells, “contributing shrill overtones that were practically inaudible.”

The scales, though pentatonic, fail to duplicate the assortment we know from the black keys of a piano. And pitch variations from gamelan to gamelan (fundamentally irreconcilable with Western tuning) amount to a science in itself.

The narrative of “A House in Bali” makes delightful reading too, despite some extreme air-brushing. McPhee’s wife, Jane Belo, a woman of means and an anthropologist, is never mentioned, though they traveled (and built the house) on her money. Bowing to the taboos of his time, McPhee passes over the awakening of his homosexuality in Bali, though the charged nature of his attachments to numerous men and boys (consummated or otherwise) is hard to miss. Impending war, one factor that drove him from Bali, is hinted at. Crackdowns by the vice squad, another factor, are not.

In shaping the stage action, the librettist Paul Schick picked out several episodes that McPhee’s readers are sure to remember: the long-drawn-out construction of the house, a comic shakedown by his native neighbors, an unsettling call from a suspected Japanese spy, a visitation by spirits of ill omen. Much of the dialogue is straight from the book; most of the rest quotes writings of the opera’s two other Western characters, Mead and the German artist Walter Spies.

As for the staging, audiences who anticipate an ornamental divertissement along the lines of the “Small House of Uncle Thomas” sequence from “The King and I” are in for a surprise. Mr. Ziporyn seems to have been thinking along these lines too, but the director, Jay Scheib, had other ideas.

“McPhee and Mead and Spies were all deeply involved in image making,” Mr. Scheib said recently between rehearsals on an iffy Skype connection from Ubud. Bali. (Signs of the times: Mr. Ziporyn remembers when the closest telephone was an hour away in the capital, Denpasar.)

“Mead was working out the methodology of visual anthropology, based on the scientific premise that you could infer more about a culture through careful photography rather than through written notes,” Mr. Scheib added. “McPhee shot hours of silent film footage of dance training and rehearsals. And Spies was documenting Balinese culture in a very interesting way through painting.”

With all this in mind Mr. Scheib has opted for extensive use of live video, giving audiences virtual eye contact with performers, even when they are confined to enclosed spaces where viewers in the auditorium cannot actually see them. This, at least, was the case in Berkeley; the production was still evolving.

At the heart of the opera, and often front and center, is Sampih, a shy, skittish country urchin who rescues McPhee from a flash flood, becomes a servant in his household and is trained, at McPhee’s urging, as a dancer. In 1952 the real Sampih achieved international stardom touring coast to coast in the United States as well as performing in London. Back home in Bali two years later, at 28, he was strangled under nebulous circumstances by a killer who was never caught.

Though the correspondences are far from exact, McPhee’s infatuation with Sampih has reminded many of Thomas Mann’s “Death in Venice,” in which the elderly, repressed aesthete Gustav von Aschenbach conceives a fatal attraction for Tadzio, an exotic youth. The opera by Benjamin Britten (a close friend of McPhee’s who for a time shared a Brooklyn brownstone with him and other arty types like Leonard Bernstein) reinforces the parallels, such as they are. Not only did Britten assign the role of Tadzio to a dancer; he also scored his music for gamelan.

The part of McPhee in Mr. Ziporyn’s opera was originally sung by Marc Molomot, who was unavailable for the current performances. His replacement is Peter Tantsits, an adventurous high tenor, who has studied the voluminous source material and McPhee’s circle in depth.

“As an opera singer it’s rare to get to play a character who existed in the flesh, and not all that long ago,” Mr. Tantsits said recently from Boston. “My first impression when I was offered the part was, ‘I’m too young to play Aschenbach,’ which is a role I’d love to do maybe in 20 years. Right now I’m 31, the same age as Colin when he went to Bali. I don’t think the relationship with Sampih was a case of sexual attraction but something more like an adoption. The way he’s described in the book is quite sensual. This is hard to talk about. I don’t think we’ve completely decided what we will decide.”

No Pandora, Mr. Ziporyn has deliberately kept a tight seal on the ambiguities.

“As McPhee presents himself in the book, he’s very transparent yet completely opaque,” Mr. Ziporyn said on a recent visit to New York. “I wanted to mirror that. I think of McPhee almost as a Nabokovian unreliable narrator, as in ‘Pale Fire,’ or even ‘Lolita,’ if that’s not too charged an analogy.

“Every quest is a quest for yourself. In going to Bali, McPhee was looking for his own artistic or personal essence. ‘I’ll always be the outsider,’ he said after he’d been there for years. He was talking about the music, he was talking about Sampih, and he was speaking in general. I wanted to convey that sense and let viewers draw their own conclusions.”

October 8, 2010

Celebrating A Gift From Bali: Delicious Confusion

By MATTHEW GUREWITSCH

NO longer quite the inaccessible Shangri-La of antique travelogue, Bali remains, for artists of all kinds and seekers of a spiritual bent, an isle of pristine enchantments. To musicians with or without the cosmic baggage, the fascination lies in the intricately layered pulse and shimmer of the gamelan, the indigenous form of orchestral ensemble, dominated by percussion and associated for centuries with Balinese ritual and devotion.

Since the 1980s the clarinetist and composer Evan Ziporyn has made the pilgrimage often. His new opera, “A House in Bali,” celebrates his forerunner Colin McPhee, a Canadian-born composer and scholar best remembered by fellow acolytes of Bali’s musical heritage. Happening on a few scratchy phonograph records from Bali in 1929, McPhee found his calling. If not for him, the traditions that flourish today might be extinct.

The opera is based mainly on McPhee’s memoirs of the same title, published in 1946 to a rave review in The New York Times by the anthropologist Margaret Mead, who had known McPhee in Bali. “This book,” Mead wrote, “is not only for those who would turn for a few hours from the jangle of modern life to a world where the wheeling pigeons wear bells on their feet and bamboo whistles on the tail feathers, but also for all those who need reassurance that man may again create a world made gracious and habitable by the arts.”

For logistical and sentimental reasons Mr. Ziporyn’s opera received its first, unstaged, preview in June 2009 on the steps of a temple in Ubud, a Balinese arts mecca, surrounded by spreading rice terraces and plunging ravines. The stage premiere followed three months later in Berkeley, Calif. This fall the opera reaches the East Coast, with performances in Boston and in the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival Thursday through Saturday.

The scoring is for a balanced ensemble of Western (the Bang on a Can All-Stars, of which Mr. Ziporyn is a founding member) and performers from Bali whose contributions are equal but for long stretches separate. On Oct. 30 a program of Mr. Ziporyn’s compositions in the Making Music series at Zankel Hall will include further examples of Western-Eastern fusion.

Born in Montreal in 1900, McPhee was hardly the first Western composer to thrill to the gamelan. The former Wagnerian Claude Debussy was transfixed by Balinese musicians at the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1889. The cosmopolitan Maurice Ravel was likewise taken. But it was left to McPhee to sail halfway around the globe to experience the music in its home.

For much of the 1930s he made Bali his home, studying, redeeming historic instruments from pawnbrokers, recruiting children to learn and play. He left in 1938, never to return, but worked on his magnum opus, “Music in Bali,” for the rest of his life. He had barely finished correcting the page proofs in the medical center of the University of California, Los Angeles, when he died, in 1964.

In his memoir McPhee’s evocations of gamelan music are bewitchingly specific.

“At first, as I listened from the house,” one passage begins, “the music was simply a delicious confusion, a strangely sensuous and quite unfathomable art, mysteriously aerial, aeolian, filled with joy and radiance. Each night as the music started up, I experienced the same sensation of freedom and indescribable freshness. There was none of the perfume and sultriness of so much music in the East, for there is nothing purer than the bright, clean sound of metal, cool and ringing and dissolving in the air. Nor was it personal and romantic, in the manner of our own effusive music, but rather, sound broken up into beautiful patterns.”

McPhee went on to analyze the music’s layered architecture: the “slow and chantlike” bass, the “fluid, free” melody in the middle register, the “incessant, shimmering arabesques” high in the treble, which ring, in McPhee’s phrase, “as though beaten out on a thousand little anvils.” Add to all this the punctuation of gongs in many registers, the cat’s-paws and throbbings and thunderclaps of the drums, the tiny crash of doll-size cymbals and the “final glitter” of elfin bells, “contributing shrill overtones that were practically inaudible.”

The scales, though pentatonic, fail to duplicate the assortment we know from the black keys of a piano. And pitch variations from gamelan to gamelan (fundamentally irreconcilable with Western tuning) amount to a science in itself.

The narrative of “A House in Bali” makes delightful reading too, despite some extreme air-brushing. McPhee’s wife, Jane Belo, a woman of means and an anthropologist, is never mentioned, though they traveled (and built the house) on her money. Bowing to the taboos of his time, McPhee passes over the awakening of his homosexuality in Bali, though the charged nature of his attachments to numerous men and boys (consummated or otherwise) is hard to miss. Impending war, one factor that drove him from Bali, is hinted at. Crackdowns by the vice squad, another factor, are not.

In shaping the stage action, the librettist Paul Schick picked out several episodes that McPhee’s readers are sure to remember: the long-drawn-out construction of the house, a comic shakedown by his native neighbors, an unsettling call from a suspected Japanese spy, a visitation by spirits of ill omen. Much of the dialogue is straight from the book; most of the rest quotes writings of the opera’s two other Western characters, Mead and the German artist Walter Spies.

As for the staging, audiences who anticipate an ornamental divertissement along the lines of the “Small House of Uncle Thomas” sequence from “The King and I” are in for a surprise. Mr. Ziporyn seems to have been thinking along these lines too, but the director, Jay Scheib, had other ideas.

“McPhee and Mead and Spies were all deeply involved in image making,” Mr. Scheib said recently between rehearsals on an iffy Skype connection from Ubud. Bali. (Signs of the times: Mr. Ziporyn remembers when the closest telephone was an hour away in the capital, Denpasar.)

“Mead was working out the methodology of visual anthropology, based on the scientific premise that you could infer more about a culture through careful photography rather than through written notes,” Mr. Scheib added. “McPhee shot hours of silent film footage of dance training and rehearsals. And Spies was documenting Balinese culture in a very interesting way through painting.”

With all this in mind Mr. Scheib has opted for extensive use of live video, giving audiences virtual eye contact with performers, even when they are confined to enclosed spaces where viewers in the auditorium cannot actually see them. This, at least, was the case in Berkeley; the production was still evolving.

At the heart of the opera, and often front and center, is Sampih, a shy, skittish country urchin who rescues McPhee from a flash flood, becomes a servant in his household and is trained, at McPhee’s urging, as a dancer. In 1952 the real Sampih achieved international stardom touring coast to coast in the United States as well as performing in London. Back home in Bali two years later, at 28, he was strangled under nebulous circumstances by a killer who was never caught.

Though the correspondences are far from exact, McPhee’s infatuation with Sampih has reminded many of Thomas Mann’s “Death in Venice,” in which the elderly, repressed aesthete Gustav von Aschenbach conceives a fatal attraction for Tadzio, an exotic youth. The opera by Benjamin Britten (a close friend of McPhee’s who for a time shared a Brooklyn brownstone with him and other arty types like Leonard Bernstein) reinforces the parallels, such as they are. Not only did Britten assign the role of Tadzio to a dancer; he also scored his music for gamelan.

The part of McPhee in Mr. Ziporyn’s opera was originally sung by Marc Molomot, who was unavailable for the current performances. His replacement is Peter Tantsits, an adventurous high tenor, who has studied the voluminous source material and McPhee’s circle in depth.

“As an opera singer it’s rare to get to play a character who existed in the flesh, and not all that long ago,” Mr. Tantsits said recently from Boston. “My first impression when I was offered the part was, ‘I’m too young to play Aschenbach,’ which is a role I’d love to do maybe in 20 years. Right now I’m 31, the same age as Colin when he went to Bali. I don’t think the relationship with Sampih was a case of sexual attraction but something more like an adoption. The way he’s described in the book is quite sensual. This is hard to talk about. I don’t think we’ve completely decided what we will decide.”

No Pandora, Mr. Ziporyn has deliberately kept a tight seal on the ambiguities.

“As McPhee presents himself in the book, he’s very transparent yet completely opaque,” Mr. Ziporyn said on a recent visit to New York. “I wanted to mirror that. I think of McPhee almost as a Nabokovian unreliable narrator, as in ‘Pale Fire,’ or even ‘Lolita,’ if that’s not too charged an analogy.

“Every quest is a quest for yourself. In going to Bali, McPhee was looking for his own artistic or personal essence. ‘I’ll always be the outsider,’ he said after he’d been there for years. He was talking about the music, he was talking about Sampih, and he was speaking in general. I wanted to convey that sense and let viewers draw their own conclusions.”

Affordable Starbucks brew any time

http://lifestyle.inquirer.net/food/food/view/20101007-296371/Affordable-Starbucks-brew-any-time

A COFFEE craving doesn’t mean a mad dash to the shops anymore. Coffee lovers can now have their favorite drink any time of the day.

Starbucks introduces the Via Ready Brew—instant coffee that comes in stick packets. It’s not the three-in-one kind, though, but basic coffee granules that mimic the exact taste, aroma and flavor of a Starbucks brew.

“Via is made of 100-percent natural roasted Arabica coffee made through the patent-pending Micro Ground Technology, which captures the quality of our whole-bean coffee,” said Cos LaPorta, Starbucks Coffee Asia-Pacific president during the recent launch at 6750, Ayala Avenue, Makati. “It’s free of by-products or chemicals, has the same body and rich flavor, but this time, you just have to add hot water.”

Starbucks Via comes in three variants: Italian Roast, extra bold (red box); Columbia, Medium (orange box); and Italian Roast, decaf (blue box). All are available in packs of three (P130) and box of 12 (P450 for regular, and P470 for decaf). That means you can have coffee for around P50 per cup—much cheaper than ordering a short latté at P90.

Is this a move to make Starbucks coffee more affordable for Filipinos?

It’s an advantage said LaPorta, but Via’s purpose is to make coffee more accessible and available.

“Via’s tagline ‘Never Be Without Great Coffee’ means you can have it even if you are traveling, in the office, on the mountains, on the beach.”

Social activity

Starbucks, a 40-year-old establishment, has 160 stores in the country since it opened it’s first branch in 1997. The Philippines is the third country outside North America to offer Via, which is available in the US, Canada, UK and Japan. Such is the demand for Starbucks products here where coffee is a staple drink and “having coffee” has evolved into a social activity.

Some Starbucks branches held a challenge where customers were given samples of freshly brewed coffee and Via mix.

“They can’t tell the difference,” said Noey Lopez, president of Rustan Coffee Corp., local franchise holder of Starbucks.

Coffee education is also practiced in Starbucks according to LaPorta. Employees undergo a Coffee Masters program where they are trained in all aspects of coffee—kinds, purchasing, food pairings and presentation.

“For example, if someone asks for a low-calorie drink, they offer brewed coffee, non-fat lattés, Café Americano, Frappuccino Light or shaken iced tea,” he added.

Iced Coffee with Milk

¾ cold water

¼ c cold milk

Pour water and milk in a tall glass. Add Starbucks Via Ready Brew and stir. Sweeten to taste and top with ice.

Coffee Soda

1 packet via

1 c sparkling water

Sugar, honey, agave or vanilla syrup

Put Via in tall glass, add small amount of sparkling water, stir to dissolve. Pour in remaining sparkling water, sweeten to taste.

Mocha Malted Milkshake

1 packet Starbucks Via

½ c cold milk

1 c chocolate ice cream

2 tbsp malted milk powder

Blend together and serve.

Caramel Mocha Milkshake

Follow instructions for Mocha Malted Milkshake but substitute vanilla ice cream for chocolate and add caramel sauce instead of malted milk powder.

A COFFEE craving doesn’t mean a mad dash to the shops anymore. Coffee lovers can now have their favorite drink any time of the day.

Starbucks introduces the Via Ready Brew—instant coffee that comes in stick packets. It’s not the three-in-one kind, though, but basic coffee granules that mimic the exact taste, aroma and flavor of a Starbucks brew.

“Via is made of 100-percent natural roasted Arabica coffee made through the patent-pending Micro Ground Technology, which captures the quality of our whole-bean coffee,” said Cos LaPorta, Starbucks Coffee Asia-Pacific president during the recent launch at 6750, Ayala Avenue, Makati. “It’s free of by-products or chemicals, has the same body and rich flavor, but this time, you just have to add hot water.”

Starbucks Via comes in three variants: Italian Roast, extra bold (red box); Columbia, Medium (orange box); and Italian Roast, decaf (blue box). All are available in packs of three (P130) and box of 12 (P450 for regular, and P470 for decaf). That means you can have coffee for around P50 per cup—much cheaper than ordering a short latté at P90.

Is this a move to make Starbucks coffee more affordable for Filipinos?

It’s an advantage said LaPorta, but Via’s purpose is to make coffee more accessible and available.

“Via’s tagline ‘Never Be Without Great Coffee’ means you can have it even if you are traveling, in the office, on the mountains, on the beach.”

Social activity

Starbucks, a 40-year-old establishment, has 160 stores in the country since it opened it’s first branch in 1997. The Philippines is the third country outside North America to offer Via, which is available in the US, Canada, UK and Japan. Such is the demand for Starbucks products here where coffee is a staple drink and “having coffee” has evolved into a social activity.

Some Starbucks branches held a challenge where customers were given samples of freshly brewed coffee and Via mix.

“They can’t tell the difference,” said Noey Lopez, president of Rustan Coffee Corp., local franchise holder of Starbucks.

Coffee education is also practiced in Starbucks according to LaPorta. Employees undergo a Coffee Masters program where they are trained in all aspects of coffee—kinds, purchasing, food pairings and presentation.

“For example, if someone asks for a low-calorie drink, they offer brewed coffee, non-fat lattés, Café Americano, Frappuccino Light or shaken iced tea,” he added.

Iced Coffee with Milk

¾ cold water

¼ c cold milk

Pour water and milk in a tall glass. Add Starbucks Via Ready Brew and stir. Sweeten to taste and top with ice.

Coffee Soda

1 packet via

1 c sparkling water

Sugar, honey, agave or vanilla syrup

Put Via in tall glass, add small amount of sparkling water, stir to dissolve. Pour in remaining sparkling water, sweeten to taste.

Mocha Malted Milkshake

1 packet Starbucks Via

½ c cold milk

1 c chocolate ice cream

2 tbsp malted milk powder

Blend together and serve.

Caramel Mocha Milkshake

Follow instructions for Mocha Malted Milkshake but substitute vanilla ice cream for chocolate and add caramel sauce instead of malted milk powder.

A bitter future: People could pay more for coffee

Original Story

Coffee lovers may soon need to dig deeper into their pockets to enjoy a cup of coffee in coffee shops ranging from global brands such as Starbucks, or even traditional street side warung kopi (coffee shop).

This is because negotiators from 193 nations are looking to adopt the Nagoya Protocol on access and benefit sharing of genetic resources. This protocol, if adopted, would allow countries to claim royalties on their genetic resources, including coffee.

The problem is that coffee is not native to Indonesia, the world’s fourth-largest producer of the bean. It was initially brought here from Brazil or South Africa by the Dutch.

The country of origin of genetic resources, including coffee, will therefore be among the hottest topics on the agenda at an international conference on biodiversity in Nagoya, Japan, next month, Hary Alexander, one of 70 negotiators Indonesia will send to the conference, told The Jakarta Post on Saturday.

After years of intensive talks, negotiators remain at odds on benefit sharing in the Nagoya Protocol.

Developed nations, which have long been users of genetic resources from developing countries, want benefit sharing calculations to take effect from when the Nagoya protocol is adopted.

Some countries proposed the benefit sharing be calculated before 1992, when the UN Convention on Biological Diversity was set up.

Indonesia, a country with one of the highest levels of biodiversity in the world, has proposed that all calculations on benefit sharing be made after 1992.

“If the conference agrees on calculations made before 1992, we have to pay high royalties, including for coffee, palm oil or sugarcane,” Hary said. “The royalties would be paid to the country of origin of the genetic resource.”

He said the genetic sources of coffee, palm oil or sugarcane were from Brazil or South Africa but that “many of our businesspeople remain unaware about the threat”.

Indonesia is struggling to adapt to the protocol. The benefit sharing could be in the form of money, capacity building or technology transfers.

Environment Ministry official Utami Andayani said many foreign researchers took samples of genetic resources from plants, animals or microorganisms from Indonesia, home to 10 percent of the world’s flowering plant species and 12 percent of all mammals.

Many of Indonesia’s species — and more than half of the archipelago’s plant species — are endemic, not found anywhere else on Earth.

But with massive forest loss from illegal logging, forest conversion and forest fires, 140 species of birds and 63 species of mammals are categorized as threatened.

Coffee lovers may soon need to dig deeper into their pockets to enjoy a cup of coffee in coffee shops ranging from global brands such as Starbucks, or even traditional street side warung kopi (coffee shop).

This is because negotiators from 193 nations are looking to adopt the Nagoya Protocol on access and benefit sharing of genetic resources. This protocol, if adopted, would allow countries to claim royalties on their genetic resources, including coffee.

The problem is that coffee is not native to Indonesia, the world’s fourth-largest producer of the bean. It was initially brought here from Brazil or South Africa by the Dutch.

The country of origin of genetic resources, including coffee, will therefore be among the hottest topics on the agenda at an international conference on biodiversity in Nagoya, Japan, next month, Hary Alexander, one of 70 negotiators Indonesia will send to the conference, told The Jakarta Post on Saturday.

After years of intensive talks, negotiators remain at odds on benefit sharing in the Nagoya Protocol.

Developed nations, which have long been users of genetic resources from developing countries, want benefit sharing calculations to take effect from when the Nagoya protocol is adopted.

Some countries proposed the benefit sharing be calculated before 1992, when the UN Convention on Biological Diversity was set up.

Indonesia, a country with one of the highest levels of biodiversity in the world, has proposed that all calculations on benefit sharing be made after 1992.

“If the conference agrees on calculations made before 1992, we have to pay high royalties, including for coffee, palm oil or sugarcane,” Hary said. “The royalties would be paid to the country of origin of the genetic resource.”

He said the genetic sources of coffee, palm oil or sugarcane were from Brazil or South Africa but that “many of our businesspeople remain unaware about the threat”.

Indonesia is struggling to adapt to the protocol. The benefit sharing could be in the form of money, capacity building or technology transfers.

Environment Ministry official Utami Andayani said many foreign researchers took samples of genetic resources from plants, animals or microorganisms from Indonesia, home to 10 percent of the world’s flowering plant species and 12 percent of all mammals.

Many of Indonesia’s species — and more than half of the archipelago’s plant species — are endemic, not found anywhere else on Earth.

But with massive forest loss from illegal logging, forest conversion and forest fires, 140 species of birds and 63 species of mammals are categorized as threatened.

Indonesia's Sulawesi September coffee exports rise

Indonesia's Sulawesi September coffee exports rise

JAKARTA (October 06, 2010) : Indonesia's coffee bean exports from the main growing island of Sulawesi rose 9.2 percent in September from a year ago, indicating adequate supplies despite unusually heavy rains, trade data showed on Tuesday. An increase in supply from Indonesia could further soften cocoa prices which have been under pressure because of a possible bumper harvest in African producers.

Liffe cocoa prices hit a one-year low last month on improved West African crop prospects. Indonesia shipped 18,849 tonnes of cocoa beans in September, up from 17,264 tonnes in the same month a year ago, trade data showed, helped by government efforts to boost production.

"Production from Central Sulawesi is quite high, after the cocoa programme was launched," said Herman Agam, chairman of the Indonesia Cocoa Association, or Askindo, for the Central Sulawesi branch. "That allow us to have more beans to meet demand," he said. Central Sulawesi shipped 53 percent of Sulawesi's cocoa bean exports in September. Indonesia, the world's third-biggest cocoa producer after Ivory Coast and Ghana, exports beans mostly to grinders in Malaysia, the United States, and Brazil.

Exports for January-September rose 8.65 percent to 210,328.44 tonnes, from 193,575.95 tonnes in the same period a year ago, indicating that a recent monthly export tax applied on cocoa beans has not slowed overseas shipment. The Indonesian government slapped an export tax on locally grown cocoa beans in April in an effort to encourage the retention of fermented beans for local grinding. It was the first time cocoa beans have been subjected to an export tax, set at 5 percent for October.

JAKARTA (October 06, 2010) : Indonesia's coffee bean exports from the main growing island of Sulawesi rose 9.2 percent in September from a year ago, indicating adequate supplies despite unusually heavy rains, trade data showed on Tuesday. An increase in supply from Indonesia could further soften cocoa prices which have been under pressure because of a possible bumper harvest in African producers.

Liffe cocoa prices hit a one-year low last month on improved West African crop prospects. Indonesia shipped 18,849 tonnes of cocoa beans in September, up from 17,264 tonnes in the same month a year ago, trade data showed, helped by government efforts to boost production.

"Production from Central Sulawesi is quite high, after the cocoa programme was launched," said Herman Agam, chairman of the Indonesia Cocoa Association, or Askindo, for the Central Sulawesi branch. "That allow us to have more beans to meet demand," he said. Central Sulawesi shipped 53 percent of Sulawesi's cocoa bean exports in September. Indonesia, the world's third-biggest cocoa producer after Ivory Coast and Ghana, exports beans mostly to grinders in Malaysia, the United States, and Brazil.

Exports for January-September rose 8.65 percent to 210,328.44 tonnes, from 193,575.95 tonnes in the same period a year ago, indicating that a recent monthly export tax applied on cocoa beans has not slowed overseas shipment. The Indonesian government slapped an export tax on locally grown cocoa beans in April in an effort to encourage the retention of fermented beans for local grinding. It was the first time cocoa beans have been subjected to an export tax, set at 5 percent for October.

Science Matters: Shady practices are good when it comes to coffee

Original Story

Coffee is the second most traded commodity in the world, after oil. And as with oil, the massive scale of production necessary to meet our insatiable demand for coffee results in an enormous ecological footprint. According the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, more than seven million tonnes of coffee will be produced worldwide this year.

The thirst for coffee is growing rapidly in developing countries, like Indonesia, where coffee beans are grown and exported. And while citizens of wealthier nations are cutting their coffee consumption, people in Africa and South America are drinking more - thanks to increasing household incomes, population growth, changing tastes, and successful marketing. The U.S.-based Starbucks coffee chain has even announced that it will open a shop in post-conflict Algeria, with plans to expand to 30 stores in Africa over the next two years.

With so many people drinking coffee (63 per cent of Canadians drink it daily, on average 2.6 cups per day), growers have industrialized production to meet demand. They've done this by establishing high-yield monoculture plantations, spraying toxic pesticides to control unwanted insects and plant pathogens, and even developing genetically modified varieties that allow traditionally shade-grown coffee, like arabica, to be grown under more economically productive conditions in partial or full sunlight.

These industrial agricultural practices have proven successful in ensuring a steady supply of beans to world markets, but the environmental costs associated with much of the coffee consumed worldwide is too high, according to many scientists who study the industry and its impacts.

Most coffee sold in Canada is grown in open plantations on land that was once tropical or subtropical forest. Since the early 1970s, huge swaths of natural rain forest have been cleared in coffee-producing nations such as Mexico, as the industry has shifted from traditional shade production to "sun-grown". A sun-grown variety such as robusta can be planted at more than three times the density of arabica shade coffee. Because of this, most of the mass-produced and instant coffees you see on supermarket shelves are grown in this way.

According to Bridget Stutchbury, an internationally renowned bird expert who has studied the impacts of coffee production on neotropical birds, "Sun coffee is not a self-sufficient ecosystem - it can only be grown with large amounts of fertilizer, fungicides, herbicides and pesticides. There are no trees to shade the coffee plants and soil from the downpours of tropical rains; soil erosion and leaching is a big problem in sun coffee farms."

On top of that, sun-coffee plantations provide little habitat for sensitive species, such as neotropical migratory birds like the hooded warbler, which are threatened because of the loss of their rain-forest habitat.

Troubled by the considerable environmental and social footprint of their favourite beverage, many consumers are looking for coffee that has been certified as organic, Fair Trade, or otherwise sustainably grown. But with so many choices, and confusing and difficult-to-verify environmental claims by businesses, experts recommend that you choose coffee that has been triple certified: organic, Fair Trade, and "shade grown".

Although it won't replace natural forests, growing coffee in shade using agro-ecosystem techniques does provide extensive understory and canopy cover from a diversity of tropical trees, providing a refuge for butterflies, birds, and other wildlife. Studies have shown that shade coffee plantations can provide habitat approaching natural conditions. For instance, a study in the El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve in southern Mexico found that the number of migratory bird species inhabiting a heavily shaded coffee plantation (30 to 35 species) approached that of a natural rain forest (35 to 40 species). In contrast, sun coffee plantations were used by fewer than five species.

As with food labelled organic or Fair Trade, consumers need a credible certification system to guarantee that their cup of coffee has been produced in a way that doesn't harm bird and other wildlife habitat. One credible certification system for shade coffee is the "Bird Friendly" eco-label, which is awarded to producers who follow a rigorous audit and verification process by the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center.

Switching to certified shade-grown coffee for your morning cup of joe won't save the planet on its own, but it is one more simple way to lessen your environmental impact.

---

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author, and chair of the David Suzuki Foundation. Faisal Moola is the director of science at the foundation (www.davidsuzuki.org).

Coffee is the second most traded commodity in the world, after oil. And as with oil, the massive scale of production necessary to meet our insatiable demand for coffee results in an enormous ecological footprint. According the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, more than seven million tonnes of coffee will be produced worldwide this year.

The thirst for coffee is growing rapidly in developing countries, like Indonesia, where coffee beans are grown and exported. And while citizens of wealthier nations are cutting their coffee consumption, people in Africa and South America are drinking more - thanks to increasing household incomes, population growth, changing tastes, and successful marketing. The U.S.-based Starbucks coffee chain has even announced that it will open a shop in post-conflict Algeria, with plans to expand to 30 stores in Africa over the next two years.

With so many people drinking coffee (63 per cent of Canadians drink it daily, on average 2.6 cups per day), growers have industrialized production to meet demand. They've done this by establishing high-yield monoculture plantations, spraying toxic pesticides to control unwanted insects and plant pathogens, and even developing genetically modified varieties that allow traditionally shade-grown coffee, like arabica, to be grown under more economically productive conditions in partial or full sunlight.

These industrial agricultural practices have proven successful in ensuring a steady supply of beans to world markets, but the environmental costs associated with much of the coffee consumed worldwide is too high, according to many scientists who study the industry and its impacts.

Most coffee sold in Canada is grown in open plantations on land that was once tropical or subtropical forest. Since the early 1970s, huge swaths of natural rain forest have been cleared in coffee-producing nations such as Mexico, as the industry has shifted from traditional shade production to "sun-grown". A sun-grown variety such as robusta can be planted at more than three times the density of arabica shade coffee. Because of this, most of the mass-produced and instant coffees you see on supermarket shelves are grown in this way.

According to Bridget Stutchbury, an internationally renowned bird expert who has studied the impacts of coffee production on neotropical birds, "Sun coffee is not a self-sufficient ecosystem - it can only be grown with large amounts of fertilizer, fungicides, herbicides and pesticides. There are no trees to shade the coffee plants and soil from the downpours of tropical rains; soil erosion and leaching is a big problem in sun coffee farms."

On top of that, sun-coffee plantations provide little habitat for sensitive species, such as neotropical migratory birds like the hooded warbler, which are threatened because of the loss of their rain-forest habitat.

Troubled by the considerable environmental and social footprint of their favourite beverage, many consumers are looking for coffee that has been certified as organic, Fair Trade, or otherwise sustainably grown. But with so many choices, and confusing and difficult-to-verify environmental claims by businesses, experts recommend that you choose coffee that has been triple certified: organic, Fair Trade, and "shade grown".

Although it won't replace natural forests, growing coffee in shade using agro-ecosystem techniques does provide extensive understory and canopy cover from a diversity of tropical trees, providing a refuge for butterflies, birds, and other wildlife. Studies have shown that shade coffee plantations can provide habitat approaching natural conditions. For instance, a study in the El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve in southern Mexico found that the number of migratory bird species inhabiting a heavily shaded coffee plantation (30 to 35 species) approached that of a natural rain forest (35 to 40 species). In contrast, sun coffee plantations were used by fewer than five species.

As with food labelled organic or Fair Trade, consumers need a credible certification system to guarantee that their cup of coffee has been produced in a way that doesn't harm bird and other wildlife habitat. One credible certification system for shade coffee is the "Bird Friendly" eco-label, which is awarded to producers who follow a rigorous audit and verification process by the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center.

Switching to certified shade-grown coffee for your morning cup of joe won't save the planet on its own, but it is one more simple way to lessen your environmental impact.

---

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author, and chair of the David Suzuki Foundation. Faisal Moola is the director of science at the foundation (www.davidsuzuki.org).

La Nina, Heavy Rains Hurt Production of Commodities

http://www.thejakartaglobe.com/business/la-nina-heavy-rains-hurt-production-of-commodities/397167

Jakarta. Unusually heavy rainfall brought on by the La Nina weather phenomenon have hammered Indonesia in recent months, leading to a pronounced drop in resource extraction and agricultural output.

The unusually wet weather has resulted in projections of slumping export volumes of tin, coal, coffee, palm oil and other commodities.

The Trade Ministry said on Monday that tin shipments from Indonesia, the world’s largest exporter of the metal, may drop 19 percent this year, adding to signs of a trade slump that has helped make tin this year’s best performing base-metal by price.

Exports could plunge to about 80,000 metric tons in 2010, down from 99,287 tons in 2009, said Alberth Tubogu, export director for mining and industry products at the Trade Ministry.

His prediction is in line with an August forecast from the Energy Ministry for a 20 percent decline in output.

According to the Trade Ministry, tin shipments from Indonesia in the first seven months of this year fell 12 percent from a year earlier to 52,133 tons.

Alberth said “unpredictable weather” has affected tin production in Bangka-Belitung Islands, the province that accounts for most of the nation’s production.

“Some producers may use their inventory to increase sales now that the price is gaining, but I doubt it will help much,” Alberth said.

“I spoke with exporters last week and they said they don’t have a lot of tin stockpiles — especially the small smelters — after heavy rain reduced ore supplies.”

Macquarie Group warned this month that global tin supply may lag behind usage “through next year at least,” bolstering prices.

Accordingly, tin futures on the London Metal Exchange have rallied to their highest price since July 2008, driven by the fall in supplies from Indonesia, lower stockpiles and rising demand.

Tin, used as packaging and solder, has advanced about 40 percent in London this year, beating second-placed nickel’s 27 percent jump.

The contract, which reached a record $25,500 a ton in May 2008, peaked at $23,800 on Sept. 17 and traded at $23,702 at 4:29 p.m. in Singapore on Monday after gaining 0.4 percent.

Meanwhile, Rachim Kartabrata, executive secretary of the Indonesian Coffee Exporters Association (AEKI), told the Jakarta Globe last week that coffee exports this year would drop by about 15 percent, from 400,000 tons to 340,000 tons.

Rachim said prolonged rain in South Sumatra, a center of coffee production, was partly to blame, as were lower levels of stock left over from last year.

Suharto Honggokusumo, executive director of the Indonesian Rubber Producers Association (Gapkindo), told the Globe that the heavy rain had limited the production of rubber tappers.

But he said export levels would hold steady thanks to a 24 percent surge in exports during the first half of this year compared to the same period last year.

The Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics Agency (BMKG) said last month that the country was experiencing its most extreme weather on record, including unusually heavy rain linked to La Nina. La Nina is expected to persist through early 2011.

The Agriculture Ministry said the extreme weather had affected agricultural output, especially in Java, of melons, mangoes and mushrooms.

The Indonesian Coal Mining Association (APBI) and the Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (Gapki) said last month that rain had hit their commodities.

The APBI said national output was likely to miss its target, while Gapki said output could fall 10 percent this year.

Reuters, JG

Jakarta. Unusually heavy rainfall brought on by the La Nina weather phenomenon have hammered Indonesia in recent months, leading to a pronounced drop in resource extraction and agricultural output.

The unusually wet weather has resulted in projections of slumping export volumes of tin, coal, coffee, palm oil and other commodities.

The Trade Ministry said on Monday that tin shipments from Indonesia, the world’s largest exporter of the metal, may drop 19 percent this year, adding to signs of a trade slump that has helped make tin this year’s best performing base-metal by price.

Exports could plunge to about 80,000 metric tons in 2010, down from 99,287 tons in 2009, said Alberth Tubogu, export director for mining and industry products at the Trade Ministry.

His prediction is in line with an August forecast from the Energy Ministry for a 20 percent decline in output.

According to the Trade Ministry, tin shipments from Indonesia in the first seven months of this year fell 12 percent from a year earlier to 52,133 tons.

Alberth said “unpredictable weather” has affected tin production in Bangka-Belitung Islands, the province that accounts for most of the nation’s production.

“Some producers may use their inventory to increase sales now that the price is gaining, but I doubt it will help much,” Alberth said.

“I spoke with exporters last week and they said they don’t have a lot of tin stockpiles — especially the small smelters — after heavy rain reduced ore supplies.”

Macquarie Group warned this month that global tin supply may lag behind usage “through next year at least,” bolstering prices.

Accordingly, tin futures on the London Metal Exchange have rallied to their highest price since July 2008, driven by the fall in supplies from Indonesia, lower stockpiles and rising demand.

Tin, used as packaging and solder, has advanced about 40 percent in London this year, beating second-placed nickel’s 27 percent jump.

The contract, which reached a record $25,500 a ton in May 2008, peaked at $23,800 on Sept. 17 and traded at $23,702 at 4:29 p.m. in Singapore on Monday after gaining 0.4 percent.

Meanwhile, Rachim Kartabrata, executive secretary of the Indonesian Coffee Exporters Association (AEKI), told the Jakarta Globe last week that coffee exports this year would drop by about 15 percent, from 400,000 tons to 340,000 tons.

Rachim said prolonged rain in South Sumatra, a center of coffee production, was partly to blame, as were lower levels of stock left over from last year.

Suharto Honggokusumo, executive director of the Indonesian Rubber Producers Association (Gapkindo), told the Globe that the heavy rain had limited the production of rubber tappers.

But he said export levels would hold steady thanks to a 24 percent surge in exports during the first half of this year compared to the same period last year.

The Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics Agency (BMKG) said last month that the country was experiencing its most extreme weather on record, including unusually heavy rain linked to La Nina. La Nina is expected to persist through early 2011.

The Agriculture Ministry said the extreme weather had affected agricultural output, especially in Java, of melons, mangoes and mushrooms.

The Indonesian Coal Mining Association (APBI) and the Indonesian Palm Oil Producers Association (Gapki) said last month that rain had hit their commodities.

The APBI said national output was likely to miss its target, while Gapki said output could fall 10 percent this year.

Reuters, JG

What’s Behind Your Cup of Joe?

Ah, coffee. What would we do without you? For centuries, people have worshiped the brew. It has long been such a prominent feature in social life that it has been memorialized in music, poems, literature, and film. For many in the United States, coffee, anyway you brew it, is an important part of a daily routine. It is habitual–perhaps even ritual. It is a stimulating narcotic, experienced as a need, and can produce emotional sensations. It is often used as a reward to mark goals achieved–”Just ten more TPS reports and I can go for a coffee break!” It is a place to go, a state of mind, a social occasion, and a source of comfort for over half the adult population of the U.S. on a daily basis.

Full (original) story Here

Full (original) story Here

Life & Style » Travel July 26, 2010 Bali - A place in time DEEPA ALEXANDER

FROM: http://www.thehindu.com/life-and-style/travel/article534678.ece

Where terraced fields swoop down on sandy beaches, and almond-eyed dancers enthrall in ancient temples

The lingering fragrance of frangipani…I wake up to it. The garland that greeted my arrival at Bali now adorns a deep rattan chair. My room at the plush Hotel Aston Kuta overlooks the Indian Ocean and the island's green landscape with its overwhelming Hindu aura and perpetual holiday vibe.

I head to the sea, and dig my feet into the warm sand to watch surfers ride the waves. Sarongs paint Kuta beach in all colours, and clouds skirt the edges of the water. Kuta, just around the bend from Ngurah Rai airport, is packed with pubs, posh restaurants, malls, hotels and money-changers. This is a part of Bali that resembles a music video.

FULL STORY

Where terraced fields swoop down on sandy beaches, and almond-eyed dancers enthrall in ancient temples

The lingering fragrance of frangipani…I wake up to it. The garland that greeted my arrival at Bali now adorns a deep rattan chair. My room at the plush Hotel Aston Kuta overlooks the Indian Ocean and the island's green landscape with its overwhelming Hindu aura and perpetual holiday vibe.

I head to the sea, and dig my feet into the warm sand to watch surfers ride the waves. Sarongs paint Kuta beach in all colours, and clouds skirt the edges of the water. Kuta, just around the bend from Ngurah Rai airport, is packed with pubs, posh restaurants, malls, hotels and money-changers. This is a part of Bali that resembles a music video.

FULL STORY

Something different, aside from coffe: Bali's Travel Boom: Eat, Pray, Love Tourism

FROM: http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,2005158,00.html

On a still road in Pengostanan Village in Bali's central foothills, a dull, blue-stained signboard points toward the house of the medicine man. Ketut Liyer is a ninth generation healer of undecided age — "maybe 90?" he shrugs — who has never been off the Indonesian island. But the dozen or so women who crowd his compound this afternoon, their chatter in competition with the peeping of caged birds suspended from clay-roofed pavilions, have come from all over. One by one they approach the small, weathered Balinese seer with the brilliant, near-toothless smile, and have him interpret their palms, their legs, sometimes even their spines.

Today, the ladies all are "very lucky." They will each live to be one hundred and ten. In fact, most days visitors to Ketut can expect the same reading, with minor variations, but few mind. Ketut Liyer is not just a healer famed among locals, but a leading character in American author Elizabeth Gilbert's 2006 memoir Eat, Pray, Love, and his bamboo mat is an almost necessary stop on Bali's increasingly popular spiritual tourist circuit.(See a story on Bali vs. Phuket.)

At the outset of the book, which has now sold over seven million copies worldwide, the medicine man predicts that Gilbert — newly divorced, disconsolate and on assignment in Indonesia — will return to Bali and teach him English. In what follows, she escapes suburban New York and over one year indulges the senses (and above all the stomach) in Italy; quiets the mind at a West Indian ashram; and, revisiting Bali, finds new love in a Brazilian jewelry exporter. If 170-odd weeks on the New York Times Best Seller List is anything to go on, weary Americans can identify with the need to regroup on unfamiliar ground. Now, in advance of the August U.S. release of a film adaptation starring Julia Roberts, that need has given rise to a new customer for Balinese hotels, travel agencies and tour operators: the spiritual seeker.

Full Story

On a still road in Pengostanan Village in Bali's central foothills, a dull, blue-stained signboard points toward the house of the medicine man. Ketut Liyer is a ninth generation healer of undecided age — "maybe 90?" he shrugs — who has never been off the Indonesian island. But the dozen or so women who crowd his compound this afternoon, their chatter in competition with the peeping of caged birds suspended from clay-roofed pavilions, have come from all over. One by one they approach the small, weathered Balinese seer with the brilliant, near-toothless smile, and have him interpret their palms, their legs, sometimes even their spines.

Today, the ladies all are "very lucky." They will each live to be one hundred and ten. In fact, most days visitors to Ketut can expect the same reading, with minor variations, but few mind. Ketut Liyer is not just a healer famed among locals, but a leading character in American author Elizabeth Gilbert's 2006 memoir Eat, Pray, Love, and his bamboo mat is an almost necessary stop on Bali's increasingly popular spiritual tourist circuit.(See a story on Bali vs. Phuket.)

At the outset of the book, which has now sold over seven million copies worldwide, the medicine man predicts that Gilbert — newly divorced, disconsolate and on assignment in Indonesia — will return to Bali and teach him English. In what follows, she escapes suburban New York and over one year indulges the senses (and above all the stomach) in Italy; quiets the mind at a West Indian ashram; and, revisiting Bali, finds new love in a Brazilian jewelry exporter. If 170-odd weeks on the New York Times Best Seller List is anything to go on, weary Americans can identify with the need to regroup on unfamiliar ground. Now, in advance of the August U.S. release of a film adaptation starring Julia Roberts, that need has given rise to a new customer for Balinese hotels, travel agencies and tour operators: the spiritual seeker.

Full Story

Harga Kopi di Lampung Barat Anjlok

Harga Kopi di Lampung Barat Anjlok

Senin, 22 Maret 2010 07:49 WIB | Ekonomi & Bisnis | Bisnis | Dibaca 589 kali

Petani Kopi/ilustrasi. (ANTARA/Anis Efizudin)

Liwa, Lampung Barat (ANTARA News) - Harga kopi di sejumlah agen di Kabupaten Lampung Barat anjlok dan harga di pasaran mencapai Rp10.000/kg, sehingga para petani mengeluhkan rendahnya harga komoditas tersebut.

Gunawan Sabki, pengumpul kopi di Pekon (Desa) Kegeringan, Kecamatanh Batu Brak, Lampung Barat mengatakan Senin, para petani mengkhawatirkan harga masih tetap rendah pada saat musim panen mendatang.

"Petani di daerah ini belum mengerti menjaga kualitas kopi, sehingga harganya rendah," katanya.

Namun meski harga komoditas di tingkat petani hanya Rp10.000/kg, para petani sudah banyak yang menjual sebagian stok mereka kepada agen untuk mencukupi kebutuhan sehari-hari.

"Petani di Lampung Barat masih mengeluhkan kondisi harga saat ini, karena modal yang dikeluarkan tidak sebanding dengan pendapatan. Selain itu, karena kebutuhan ekonomi jelang panen raya, mereka menjual stok kopi-nya, walaupun harga masih rendah."

Data Dinas Perkebunan Kabupaten Lampung Barat menyebutkan, luas lahan kopi mencapai 60.347.70 hektare dengan hasil kopi kering per tahun mencapai 28,712 ton/ha.

Keluhan senada juga diutarakan petani kopi di desa Pekon, Kecamatan Balik Bukit, Lampung Barat, Junaidi tentang rendahnya harga komoditas tersebut.

"Harga kopi kian anjlok. Kami sangat prihatin dengan harga tersebut, tetapi mau apalagi?. Karena kebutuhan ekonomi semakin meningkat jelang panen raya, terpaksa saya menjual stok meski harga rendah," kata petani lainnya, Masnah.

Ia berharap walaupun harga rendah, tetapi diimbangi dengan perolehan panen, sehingga modal yang di keluarkan dapat kembali.

Ke depan Pemkab Lampung Barat tidak tinggal diam dan harus memiliki terobosan yang dapat meningkatkan harga dan mutu kopi, harapnya. (MH*H009/K004)

Senin, 22 Maret 2010 07:49 WIB | Ekonomi & Bisnis | Bisnis | Dibaca 589 kali

Petani Kopi/ilustrasi. (ANTARA/Anis Efizudin)

Liwa, Lampung Barat (ANTARA News) - Harga kopi di sejumlah agen di Kabupaten Lampung Barat anjlok dan harga di pasaran mencapai Rp10.000/kg, sehingga para petani mengeluhkan rendahnya harga komoditas tersebut.

Gunawan Sabki, pengumpul kopi di Pekon (Desa) Kegeringan, Kecamatanh Batu Brak, Lampung Barat mengatakan Senin, para petani mengkhawatirkan harga masih tetap rendah pada saat musim panen mendatang.

"Petani di daerah ini belum mengerti menjaga kualitas kopi, sehingga harganya rendah," katanya.

Namun meski harga komoditas di tingkat petani hanya Rp10.000/kg, para petani sudah banyak yang menjual sebagian stok mereka kepada agen untuk mencukupi kebutuhan sehari-hari.

"Petani di Lampung Barat masih mengeluhkan kondisi harga saat ini, karena modal yang dikeluarkan tidak sebanding dengan pendapatan. Selain itu, karena kebutuhan ekonomi jelang panen raya, mereka menjual stok kopi-nya, walaupun harga masih rendah."

Data Dinas Perkebunan Kabupaten Lampung Barat menyebutkan, luas lahan kopi mencapai 60.347.70 hektare dengan hasil kopi kering per tahun mencapai 28,712 ton/ha.

Keluhan senada juga diutarakan petani kopi di desa Pekon, Kecamatan Balik Bukit, Lampung Barat, Junaidi tentang rendahnya harga komoditas tersebut.

"Harga kopi kian anjlok. Kami sangat prihatin dengan harga tersebut, tetapi mau apalagi?. Karena kebutuhan ekonomi semakin meningkat jelang panen raya, terpaksa saya menjual stok meski harga rendah," kata petani lainnya, Masnah.

Ia berharap walaupun harga rendah, tetapi diimbangi dengan perolehan panen, sehingga modal yang di keluarkan dapat kembali.

Ke depan Pemkab Lampung Barat tidak tinggal diam dan harus memiliki terobosan yang dapat meningkatkan harga dan mutu kopi, harapnya. (MH*H009/K004)

Harga Kopi Arabika Menguat Didukung Kenaikan Komoditas Lain

Kamis, 25 Februari 2010 10:00 WIB

(Vibiznews – Commodity) – Pada penutupan perdagangan di bursa ICE Futures New York dini hari tadi tampak harga kopi arabika mengalami peningkatan (25/02). Harga kopi arabika menguat didukung oleh melemahnya nilai tukar dolar AS. sementara itu sebagian besar komoditas yang juga tampak menguat juga memberikan support bagi peningkatan harga kopi arabika.

Tadi malam dolar AS mengalami penurunan setelah data ekonomi berupa penjualan rumah baru mengalami penurunan. Kondisi melemahnya dolar AS mengakibatkan harga komoditas yang diperdagangkan dalam dolar menjadi lebih diminati karena harganya cenderung relative lebih murah.

Harga kopi arabika berjangka untuk kontrak pengiriman bulan Maret tampak mengalami peningkatan sebesar 10 poin (0.08%) dan ditutup pada posisi 1.3045 dolar per pon. Sementara itu harga kopi arabika untuk kontrak pengiriman bulan Mei mengalami kenaikan sebesar 60 poin (0.45%) di posisi 1.3285 dolar per pon.

Analis Vibiz Research dari Vibiz Consulting memperkirakan bahwa harga kopi arabika akan cenderung bergerak dengan mengikuti arahan dari luar pasar. Saat ini level 1.30 sen akan menjadi level support. Sementara itu level resistance akan ditemui pada 1.40 sen per pon.

(Vibiznews – Commodity) – Pada penutupan perdagangan di bursa ICE Futures New York dini hari tadi tampak harga kopi arabika mengalami peningkatan (25/02). Harga kopi arabika menguat didukung oleh melemahnya nilai tukar dolar AS. sementara itu sebagian besar komoditas yang juga tampak menguat juga memberikan support bagi peningkatan harga kopi arabika.

Tadi malam dolar AS mengalami penurunan setelah data ekonomi berupa penjualan rumah baru mengalami penurunan. Kondisi melemahnya dolar AS mengakibatkan harga komoditas yang diperdagangkan dalam dolar menjadi lebih diminati karena harganya cenderung relative lebih murah.

Harga kopi arabika berjangka untuk kontrak pengiriman bulan Maret tampak mengalami peningkatan sebesar 10 poin (0.08%) dan ditutup pada posisi 1.3045 dolar per pon. Sementara itu harga kopi arabika untuk kontrak pengiriman bulan Mei mengalami kenaikan sebesar 60 poin (0.45%) di posisi 1.3285 dolar per pon.

Analis Vibiz Research dari Vibiz Consulting memperkirakan bahwa harga kopi arabika akan cenderung bergerak dengan mengikuti arahan dari luar pasar. Saat ini level 1.30 sen akan menjadi level support. Sementara itu level resistance akan ditemui pada 1.40 sen per pon.

(Ika Akbarwati/IA/vbn)

http://vibiznews.com/news_last.php?id=7125&sub=news&month=Februari&tahun=2010&awal=10&page=commodity

Coffee Species - Arabica and Robusta

Coffee Species - Arabica and Robusta

A comparison between Arabica and Robusta the two main coffee species that make up the world coffee bean trade.

Coffee beans are the second most traded commodity on world markets, only bettered by oil. Most of us come face to face with a coffee drink almost daily but few of us realise the history, botany and process that have developed to allow this daily ritual to take place. Here is another article in the series about coffee, dealing with the two main coffee species - Arabica and Robusta, that we engage with as we enjoy that elixir of the gods.

http://knol.google.com/k/coffee-species-arabica-and-robusta#

A comparison between Arabica and Robusta the two main coffee species that make up the world coffee bean trade.

Coffee beans are the second most traded commodity on world markets, only bettered by oil. Most of us come face to face with a coffee drink almost daily but few of us realise the history, botany and process that have developed to allow this daily ritual to take place. Here is another article in the series about coffee, dealing with the two main coffee species - Arabica and Robusta, that we engage with as we enjoy that elixir of the gods.

http://knol.google.com/k/coffee-species-arabica-and-robusta#

Coffee revives as Vietnam starts stockpiling

Coffee revives as Vietnam starts stockpiling

Coffee recovered from its three-year low in London, and rebounded 2% in New York, after Colombia unveiled a 25% slide in production and Vietnam began building up stockpiles of robusta beans.

Robusta beans for March delivery closed up $9 at $1,199 a tonne in London, with the better-traded May contract jumping $23 to $1,245 a tonne.

The first price rise in four trading days followed confirmation of the start of a government-backed programme of coffee purchases by Vietnamese companies, with the aim of stockpiling 200,000 tonnes of the crop, nearly 20% of the country's annual production.

'Output should contract sharply'

Furthermore, many analysts believe the weak market which has prompted the stock-building will prompt Vietnam, the biggest robusta producer, to hold back on production.

World's biggest robusta producers, 2010-11 (year-on-year change)

1: Vietnam, 18.00m tonnes (-2.7%)

2: Brazil, 14.00m tonnes (+4.6%)

3: Indonesia, 8.25m tonnes (+3.1%)

4: India, 3.20m tonnes (-1.5%)

5: Uganda, 3.00m tonnes (+3.4%)

World: 53.99m tonnes (unchanged)

Source: Fortis Bank Nederland

"We expect prices to stabilise, since at the current low price levels output should contract sharply in Vietnam," Commerzbank analysts said.

They also took an optimist's view of a near-halving, to 22,000 tonnes, in exports of robusta beans last month from Brazil, the second-ranked producer.

"The sharp decline could be the result of higher domestic consumption, reducing the amount of robusta coffee that is available for shipments overseas," the bank said.

Colombian slide

Meanwhile, arabica coffee beans, which last week touched a five-month low, rose more than 2% in New York after Colombia reported February production at 650,000 bags (39,000 tonnes), down 218,000 bags year on year.

The figure was lower than the 700,000 bags that Colombia's coffee growers' federation had expected, although Luiz Munoz, the association's director, said that the country was still on track to hit a half-year production target of 5m bags (300,000 tonnes).

Output in Colombia, the second-biggest producer of arabica beans after Brazil, has been dented by poor weather and a replanting programme which has reduced short-term output potential.

Buy stops triggered

Technical factors also helped the arabica market, after the May contract broke through a resistance level at 132 cents a pound.

World's biggest arabica producers, 2010-11 (year-on-year change)

1: Brazil, 38.95m tonnes (+13.9%)

2: Colombia, 10.0m tonnes (+8.1%)

3: Ethiopia, 8.25m tonnes (-4.5%)

4: Peru, 4.25m tonnes (+6.3%)

5: Mexico, 4.2m tonnes (-4.5%)

World: 86.11m tonnes (+7.0%)

Source: Fortis Bank Nederland

"Getting above there set a few buy stops off," Ralph Hawes, at Sucden Financial in London, told Agrimoney.com, adding that technical analysis suggested that a close at about 132.50 cents a pound could spark a move to 136-137 cents a pound.

Coffee traders have also flagged managed funds' increasing bearishness over coffee, with short positions exceeding longs by 3,195 contracts last week, according to regulatory data.

Ironically, such movements have often, as in autumn 2008 and spring 2007, heralded an upturn in prices.

New York's May coffee contract closed up 1.3% at 132.75 cents a pound.

Coffee recovered from its three-year low in London, and rebounded 2% in New York, after Colombia unveiled a 25% slide in production and Vietnam began building up stockpiles of robusta beans.

Robusta beans for March delivery closed up $9 at $1,199 a tonne in London, with the better-traded May contract jumping $23 to $1,245 a tonne.

The first price rise in four trading days followed confirmation of the start of a government-backed programme of coffee purchases by Vietnamese companies, with the aim of stockpiling 200,000 tonnes of the crop, nearly 20% of the country's annual production.

'Output should contract sharply'

Furthermore, many analysts believe the weak market which has prompted the stock-building will prompt Vietnam, the biggest robusta producer, to hold back on production.

World's biggest robusta producers, 2010-11 (year-on-year change)

1: Vietnam, 18.00m tonnes (-2.7%)

2: Brazil, 14.00m tonnes (+4.6%)

3: Indonesia, 8.25m tonnes (+3.1%)

4: India, 3.20m tonnes (-1.5%)

5: Uganda, 3.00m tonnes (+3.4%)

World: 53.99m tonnes (unchanged)

Source: Fortis Bank Nederland

"We expect prices to stabilise, since at the current low price levels output should contract sharply in Vietnam," Commerzbank analysts said.

They also took an optimist's view of a near-halving, to 22,000 tonnes, in exports of robusta beans last month from Brazil, the second-ranked producer.

"The sharp decline could be the result of higher domestic consumption, reducing the amount of robusta coffee that is available for shipments overseas," the bank said.

Colombian slide

Meanwhile, arabica coffee beans, which last week touched a five-month low, rose more than 2% in New York after Colombia reported February production at 650,000 bags (39,000 tonnes), down 218,000 bags year on year.

The figure was lower than the 700,000 bags that Colombia's coffee growers' federation had expected, although Luiz Munoz, the association's director, said that the country was still on track to hit a half-year production target of 5m bags (300,000 tonnes).

Output in Colombia, the second-biggest producer of arabica beans after Brazil, has been dented by poor weather and a replanting programme which has reduced short-term output potential.

Buy stops triggered

Technical factors also helped the arabica market, after the May contract broke through a resistance level at 132 cents a pound.

World's biggest arabica producers, 2010-11 (year-on-year change)

1: Brazil, 38.95m tonnes (+13.9%)

2: Colombia, 10.0m tonnes (+8.1%)

3: Ethiopia, 8.25m tonnes (-4.5%)

4: Peru, 4.25m tonnes (+6.3%)

5: Mexico, 4.2m tonnes (-4.5%)

World: 86.11m tonnes (+7.0%)

Source: Fortis Bank Nederland

"Getting above there set a few buy stops off," Ralph Hawes, at Sucden Financial in London, told Agrimoney.com, adding that technical analysis suggested that a close at about 132.50 cents a pound could spark a move to 136-137 cents a pound.

Coffee traders have also flagged managed funds' increasing bearishness over coffee, with short positions exceeding longs by 3,195 contracts last week, according to regulatory data.

Ironically, such movements have often, as in autumn 2008 and spring 2007, heralded an upturn in prices.

New York's May coffee contract closed up 1.3% at 132.75 cents a pound.

Singapore launches coffee futures bourse

Singapore launches coffee futures bourse

SINGAPORE — The Singapore Commodity Exchange is set to begin robusta futures trading on April 22 this year for the coffee variety in Asia.

"The launch of Singapore Coffee Futures Contract (SICOM Coffee) is timely as Southeast Asia has grown to become the largest producer and exporter of robusta coffee. SICOM Coffee is set to play a key role in establishing an Asian benchmark price for robusta coffee," Jeremy Ang, CEO of SICOM, said.

It is a physical delivery futures contract, traded in five metric tonnes per lot. Delivery will be made via warehouse receipts representing coffee stored in bonded warehouses in HCM City or Singapore.

This delivery mechanism provides for a short delivery period and simplified logistics.

Angeline Koh, deputy director, Sector Division, Financial Markets Strategy Department of the Monetary Authority of Singapore, said: "With Viet Nam and Indonesia being the world's two largest robusta coffee producers, there are many coffee exporters and traders based in Asia.

"A well-designed coffee futures contract will serve as an effective risk management instrument for the coffee industry based in Asia. As part of the development of Singapore's commodity derivatives market, we welcome the launch of unique Asian-centric contracts."

Luong Van Tu, chairman of the Vietnam Coffee and Cocoa Association, said: "The launch of SICOM Robusta Coffee deliverable to bonded warehouses in Viet Nam is representative of Asian trade which will benefit Vietnamese coffee growers and exporters."

Victor Mah, president of the Singapore Coffee Association, said: "Asia and in particular Southeast Asia is a key player in the global robusta coffee market but lacks an Asian price discovery platform. SICOM's Coffee will offer international market participants an effective hedging tool to manage their price risk." — VNS

SINGAPORE — The Singapore Commodity Exchange is set to begin robusta futures trading on April 22 this year for the coffee variety in Asia.

"The launch of Singapore Coffee Futures Contract (SICOM Coffee) is timely as Southeast Asia has grown to become the largest producer and exporter of robusta coffee. SICOM Coffee is set to play a key role in establishing an Asian benchmark price for robusta coffee," Jeremy Ang, CEO of SICOM, said.

It is a physical delivery futures contract, traded in five metric tonnes per lot. Delivery will be made via warehouse receipts representing coffee stored in bonded warehouses in HCM City or Singapore.

This delivery mechanism provides for a short delivery period and simplified logistics.

Angeline Koh, deputy director, Sector Division, Financial Markets Strategy Department of the Monetary Authority of Singapore, said: "With Viet Nam and Indonesia being the world's two largest robusta coffee producers, there are many coffee exporters and traders based in Asia.

"A well-designed coffee futures contract will serve as an effective risk management instrument for the coffee industry based in Asia. As part of the development of Singapore's commodity derivatives market, we welcome the launch of unique Asian-centric contracts."

Luong Van Tu, chairman of the Vietnam Coffee and Cocoa Association, said: "The launch of SICOM Robusta Coffee deliverable to bonded warehouses in Viet Nam is representative of Asian trade which will benefit Vietnamese coffee growers and exporters."

Victor Mah, president of the Singapore Coffee Association, said: "Asia and in particular Southeast Asia is a key player in the global robusta coffee market but lacks an Asian price discovery platform. SICOM's Coffee will offer international market participants an effective hedging tool to manage their price risk." — VNS

Local coffee company a pick-me-up for literacy Indonesian coffee roasted right here at home

Local coffee company a pick-me-up for literacy

Indonesian coffee roasted right here at home

By Bob Morgan

(Created: Thursday, March 4, 2010 12:06 PM CST)

SUMMERDALE, Ala. — This community is no stranger to crops but coffee beans are something else. Yet, there are tons of Indonesian coffee beans right here just waiting to be roasted and turned into one of the four types of coffee that Tändük Coffee Co. makes available. (It’s pronounced Taan Dook.)

Roasted beans have complete the roasting process. Raw coffee beans have sugar in them that, once heated, begin to carmelize which gives the coffees their distinct tastes. (Bob Morgan/staff photo)

From Java, one of the Indonesian islands, to a cup of “java” locally, the world of coffee has a local flavor what with Tändük's roasting facility and warehouse in Summerdale.

The roastmaster is Kenneth Ferguson, a retired Marine major and helicopter pilot who lives in Foley at Glenlakes. How Kenneth, who has operated a Maytag business and taught at Summerdale school during retirement, became the company roaster actually begins with his son, Beau, going as an English teacher to Indonesia some years back.

After a short tour there, Beau and his wife felt led to go back to Indonesia, especially in light of the tsunami that struck the country a few years ago. The couple got involved with a village library program and Beau came up with the idea of starting a coffee company.

It was last year when Beau got a shipment of 14,000 pounds of coffee beans together and had them shipped to this area. A warehouse was found and Kenneth said they had to make some changes in the building to comply with the Health Department.

A roaster that was handmade in a “little shop” in Indonesia was shipped with along with the coffee beans.

“We made a few modifications in it,” Kenneth said of the roaster, which weighs about 2,000 pounds.

The coffee beans that arrived came from two regions in Indonesia, which is a country made up of 15,000 islands or so and is the largest Muslim country in the world by population. The beans are Sulawesi Toraja Arabica and Sumatra Mandheling Arabica. To get an idea of what a commodity coffee is in Indonesia, Kenneth notes there are five or six coffee regions on the island of Sumatra alone.