By JOHN KRICH

Considering how much I've consumed over a lifetime, it seemed remarkable that I had never seen coffee -- meaning the actual bean on the bush.

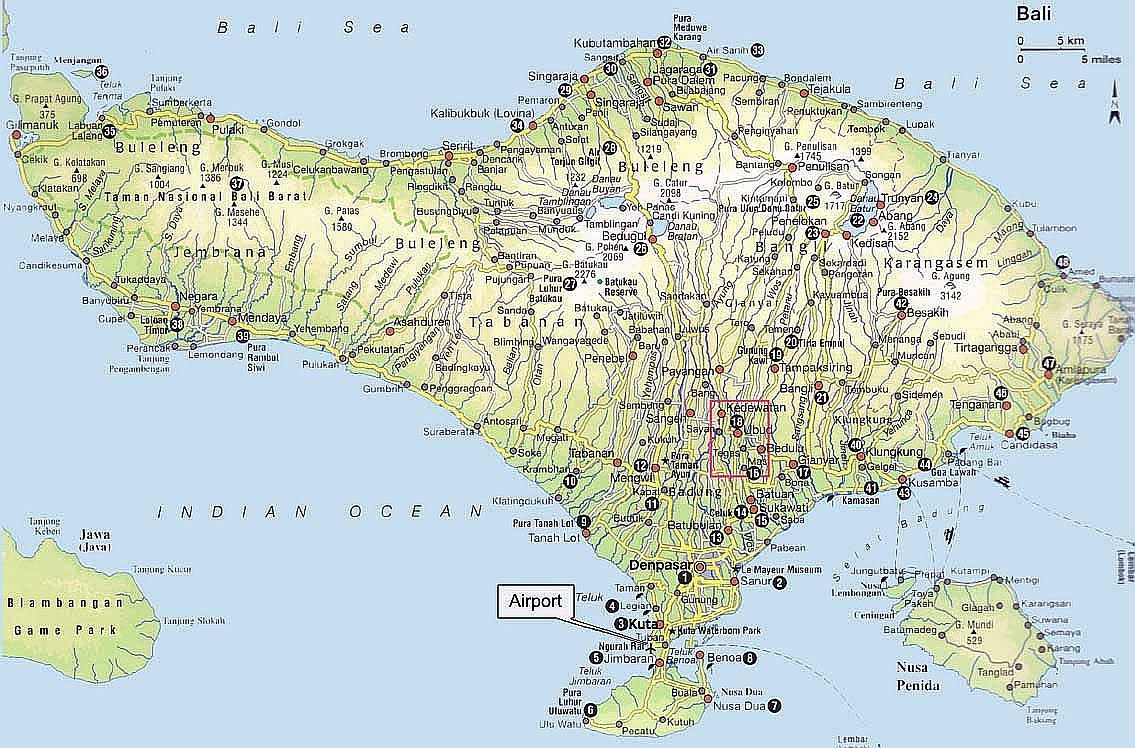

But here I was in Bali, whose coffee-growing region seemed to come, in the Balinese manner, with so much more: mountain views, temples and terraces. So on an island where nearly everything, barring the agricultural West's bull racing, can be reached within an hour and some scant meditative moments, I decided to make coffee country my day-trip destination. (There are a great range of atmospheric upcountry escapes available. A sprawling Denpasar, and even more so, the tourist strips concentrated on Bali's southernmost nub, provide ever-increasing reasons for making the attempt.)

Even the gas stations along the way come with piped-in, tinkly gamelan music. Small-town main streets are lined with delicate, statuary-festooned temple compounds, the roadside stands along the way are mostly seasonal ones for durian and jackfruit (which I sample along with, strangely enough, an avid Chinese couple from Los Angeles), and the pit stops now include one called Babi Guling (Suckling Pig) Obama.

Seeing this is an island, no matter which road you follow, you'll eventually get to the sea (with a brooding volcano or two in between.) My chosen path aims straight for Bedugul and beyond. But things start to get interesting at Pacung, where the views of rice terraces open up and the climb toward, or through, a breathtaking line-up of black peaks.

As it turns out, Bedugul isn't much but a sprawling wet market, plied by peasants in woolen caps and long-sleeved shirts that flop oversize over sarongs. Just over an hour from Denpasar's limits, the place feels like a way station in Nepal or the lower Andes, quite a shock after a morning's loll in the tub-warm waves of Jimbaran beach. It doesn't take long for microclimates to change on Bali.

I get another surprise when my driver makes a wrong left turn at the market junction. Instead of heading farther uphill toward Munduk, this road ends at the entrance to Eka Karya Botanic Garden, one of four botanic gardens run by the Indonesian Institute of Sciences. Founded in 1959, it, too defies expectations. Laid out in broad avenues and circular roads in the late Indo-fascist manner, this is no place for a brief stroll to sniff the flowers. It's more suited to a day's backpacking: 157 hectares of luxuriant, shadow-dappled high-altitude forest preserve, including numerous stands of birch. There are temples and traditional houses hidden here and there, along with obligatory rose and orchid displays. There's also a kiosk that sells herbal remedies -- based on Usada, or Balinese healing -- that are derived from native plants.

But I'm after another sort of potent plant, the kind that brings a buzz to wake me each morning. Before reaching coffee country proper, the landscape is dominated by strawberry farms. It's not exactly scenic, with much of the ground around the budding berries covered in protective plastic wrap, but one roadside farm is fronted by a "Strawberry Stop" cafe that makes a passable milkshake. It greatly improves the usual nasi goreng (fried rice).

Now the road toward Bali's north coast veers west in a precipitous rise along a ridge with magnificent views of two adjacent, elongated lakes, the larger Danau Buyan, that form the island's eerily quiet heart. While the waters below are shimmering and shallow, perfect for snapshots, there don't seem to be any boats out. I wonder whether the Balinese, never big fish-eaters, see more spiritual than material sustenance in these carpet-like waters. (Later, I read a more mundane explanation: Fertilizers have polluted the lakes, which have been receding due to sedimentation. An investment group now vows to return the area to its status as an "eco heaven.")

And soon enough, the first billboard announcing "Bali Coffee" makes a signpost for a road that leads farther up into thick mists, then down the backside of the ridge. On a clear day, the downward spiral of hairpin turns must offer stunning views of this round bowl of a valley. But it's tough in the fog to clearly identify any of the local agriculture. Fortunately, a relatively new sign directs my driver to turn down a long driveway to the Munduk Moding Plantation. Billed as a "nature resort and spa," the place turns out to be a single, Dutch-style manor house, splendidly remodeled with four rooms up top, looking out over an infinity-style pool and its five hectares of working coffee farm.

But I still don't see any of the prized crop until the staff leads me along stone steps that make a circular path around the property. At long last, I've got beans to both sides of me, and these are in the raw, not freeze-dried or in measured espresso packets. All I have to do is lift the shiny leaves of these pleasant shrubs to see clumps of the green buds that have given humanity (including me) so much inspiration. How can so nerve-jangling a fruit come with such comfortingly pretty white flowers?

At the end of the trek, I'm joined by Made, the well-spoken, tie-wearing co-founder of the place. While sipping from his plantation's best brew, he explains that he and a Dutch partner invested six billion rupiahs ($640,000) not merely to turn a profit from tourism but to help save his home region's coffee tradition, hurt by a falling water table (coffee is a thirsty crop) and long stretch of weak coffee prices over the past decade. Locals say that coffee, originally brought by Dutch colonizers, is being slowly replaced by more lucrative crops such as cocoa.

His coffee seems to go down very smoothly, until he informs me that what I am drinking is actually kopi lubak, more commonly kopi luwak, a rare treat. Brewed from beans gathered by neighboring farmers from the feces of a local, coffee-addicted species of civet (the pulpy part of the berry is digested, but the bean passes through whole), it's renowned for its lack of bitterness. (The beans do get a rinse before roasting.) I don't even realize until it's too late that I might have just downed some of the world's most expensive java (in this case, Bali).

Made's recommendation for a homemade coffee-roasting operation leads way down to the valley bottom. But after a sprint through a sudden late-afternoon downpour, I'm told the backyard operation is closed for a full-moon festival -- one of the common, if charming, hazards in touring an island that operates on its own celestial calendar. In a pinch, Bali is usually able to provide one tourist catchall someplace. Around Munduk, it's the well-publicized Ngring Ngewedang, which I fortunately don't have to pronounce because it translates roughly as -- surprise! -- "enjoying coffee."

An open patio and covered tables command a great view (should the mist clear) from a strategic turn in the road, and, before actually partaking of more local brew (or taking home souvenir packets), Joni Suhadi, a relentless friendly manager who learned his English from years on a cruise ship, narrates a full tour of the facilities.

Down a path from the cafe is a shack devoted to coffee roasting, which is done over a wood fire as the beans roll in a crude and very rusty tumbler than reminds me of a big lettuce dryer. An energetic young couple, male and female, wait under a patch of thatched shade to raise oversize pestles and take up the vigorous pounding in a stone mortar that takes the place of an electric coffee grinder here. The result is a powder that concentrates every kick from the high-octane Robusta variety; the sample I finally get to sip is blastedly strong.

My pilgrimage to coffee country is made complete with a final stop at Ulu Danu, considered one of the island's more revered "water temples." It's quite a trek from the edge of Lake Bratan and doesn't look to be a very active, though a small group of pilgrims soon hops from the back of a pickup truck to leave offerings inside its weathered walls, slightly reminiscent of a prison yard. Still, the sculpted stone turrets are atmospheric as they face out on the shallow waters. And this blackened, slightly spooky shrine just may be the perfect place to placate the gods of caffeine and calm down after too much robusta.

--John Krich is a writer based in Bangkok.

skip to main

|

skip to left sidebar

skip to right sidebar

Black as the devil, Hot as hell, Pure as an angel, Sweet as love.

Travel to Indonesia

Contact Our Team:

Raja Kelana Adventures Indonesia

Raja Kelana Adventures Indonesia

Email: putrantos2022@gmail.com

Facebook Messenger: https://www.facebook.com/putranto.sangkoyo

Our Partner

Blog Archive

-

▼

2010

(19)

-

▼

March

(9)

- Harga Kopi di Lampung Barat Anjlok

- INDONESIAN COFFEE PRICE DATABASE

- Harga Kopi Arabika Menguat Didukung Kenaikan Komod...

- Coffee Species - Arabica and Robusta

- Coffee revives as Vietnam starts stockpiling

- Singapore launches coffee futures bourse

- Local coffee company a pick-me-up for literacy In...

- Developing Geographical Indication Protection in I...

- One Hour Out: Bali Escape to the high country (f...

-

▼

March

(9)