Bali by bicycle : article from: http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2004/04/16/1082055633667.html

The lush steep steppes of Bali provides a challenge for even the most determined cyclist.

It was tough, it was wet, but Andrew Bain found unexpected delights pedalling around Bali.

The road is a river, awash with monsoonal rains. The midday sun has darkened to a candle of light and thunder resounds like cannon fire across the sullen Bali sky.

"It is God's music," Wayan assures me from inside the shelter of his roadside stall, and for him the weather is indeed a divine blessing. I am the first traveller in months to stop at his store on the outskirts of the city of Gianyar, marooned here in my sodden clothes and with my mythically deep tourist pockets. I order a second drink and another stormy hour passes.

Out in the bitumen stream a prehistoric bicycle splashes past, its rider bared to the rain but for a pair of saturated trousers that cling to his grasshopper-thin legs. Such stoicism shames me, huddled as I am in the comfort of this temporary asylum. I make my farewell to a disappointed Wayan, who assures me I am both strong and crazy, and head back out into the rain and onto my own dripping bicycle.

"You are like Neil Armstrong," Wayan proclaims, though he means Lance Armstrong, since I've just told him of my intention to cycle around Bali.

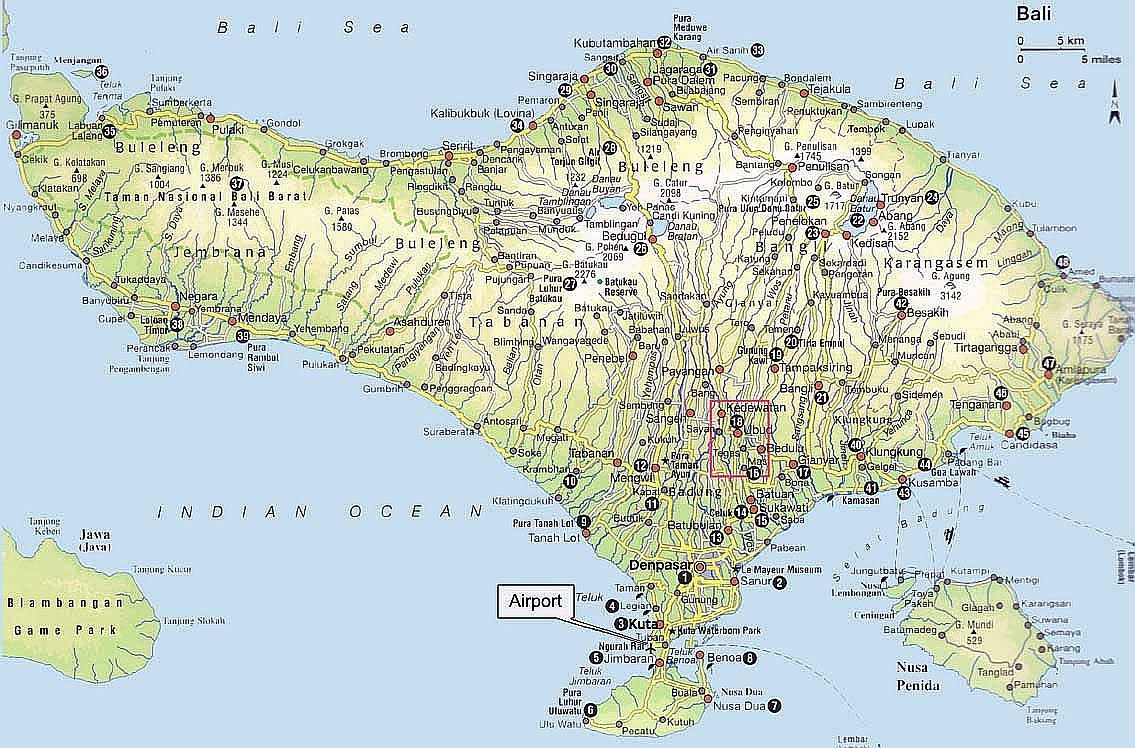

My journey had begun in Denpasar just a few hours before. If there is safety in madness it is here, cycling in the turmoil of Bali's largest city. Traffic spins as wildly as a centrifuge, trucks, cars, motorbikes, pushcarts, dogs, pedestrians and chickens doing as they please. It's disorder that's accustomed to disorder, Asia condensed to a small island, and my bicycle barely registered in its mind. I was just another pothole or chicken to be driven around.

Horns sounded without end, but within an hour I'd learned to ignore them, their language more foreign to me even than Indonesian. They seemed to say nothing and everything - hello, watch out, move aside, good luck or, simply, I have a horn. Trucks lumbered by but only one came near to hitting me, a truck named God Bless II that almost blessed me head-on.

Denpasar sprawled east to blur into Gianyar, the roadside an unholy alliance of temples, urban rice fields and stores advertising Playstation rental and the machismo of cigarettes. Quickly it became apparent that the beaches, volcanoes and lush rice terraces that monopolise Bali's tourist image would not be the cyclist's reality, fading to secondary status behind the endless string of village life. Each time I stopped for a rest, motorbikes pulled in alongside, asking the question I'd answer dozens of times each day.

"Where you go?"

Any reply would suffice. Sometimes I'd name the next village, city or tourist attraction. Other times I'd get bolder.

"To the moon," I told one motorcyclist in Gianyar, delighting in my new kinship with Neil Armstrong.

"Very good, sir."

To the continued accompaniment of God's thunderous tune I turned inland at Gianyar, onto the fertile slopes of Bali's highest and most sacred volcano, Gunung Agung. Settlement and the road snaked up the volcano and into the former royal city of Bangli. Billed by one local book as the "Cinderella of Bali tourism", Bangli is bookended by great temples: Pura Dalem Penunggekan and Pura Kehen, the island's second-largest temple, stepped into a hillside above the city. Kehen is tourist central for Bangli, yet almost every one of the souvenir stalls at its edge was shuttered. That night, I would be the only guest at either of Bangli's two hotels.

"Bali many problems," a man at Pura Kehen's entrance told me. "Bomb." And so began another discussion that echoed through my days on the island: the Kuta bombing.

Not once did I dig at Balinese memories of the blast, but they lay scattered and exposed like rubble. That night, I heard music in the street below my hotel room - guitar, tambourine and wonderfully raucous, harmonising voices. Balinese songs broken by a recurring rendition of La Bamba. I wandered outside and sat on the kerb to listen. Within minutes I was invited over for a beer and a song.

"Three years ago Bangli had many tourists, but now there are none," one of the singers explained, his face hardening like stone. "F-- Amrosi. F-- terrorist." F-- terrorist, the others sang. The same words followed me from conversation to conversation, village to village. English-speakers or not, it seemed that everybody knew this one fervent statement.

In Bangli the night never stilled and I slept fitfully. Dogs fought in the street, roosters called impatiently and people rose to begin their long days. Finally, so did the sun, etching Gunung Agung black onto the dawn sky, its peak almost 3000 metres above the city. That day my punishment would be to contour across the mountain's ribbed slopes, riding a rollercoaster of lava flows towards the island's east coast. My reward for this effort would be to disappear into the verdant folds that held some of Bali's most attractive rice terracing.

Cattle ploughed the terraces and workers stood from their river baths, immodest about their nudity, to wave as I passed.

"Where you go, sir?" they'd call, and I'd just point ahead. On through this terraced country seemed as good as anywhere.

The road crested at around 600 metres above sea level, the rice fields suddenly behind and below me and a tropical cornucopia ahead. The forest thickened and filled with rambutan, papaya, banana and salak, the Balinese "snakeskin" fruit that would virtually fuel my journey. My panniers became heavy with fruit, an anchor for what would become a difficult next day.

My plan for that day was to reach the once-burgeoning east-coast resort of Amed, only 14 kilometres from where I slept in Tirta Gangga. It could have been so easy. Instead, I doubled back and turned onto the little-used coastal road that rounded Bali's eastern tip. Fifty kilometres later I'd be cursing the most trying day of my journey.

I joined the coast at Ujung, site of an elaborate water palace, its pools now more popular with local anglers than tourists. From here the road pointed up, not following the coast at all but ascending onto the slopes of the volcano Gunung Seraya.

Through Seraya village the road climbed 200 metres, sweat pouring from my body in the relentless humidity, making me wetter than I'd been in some downpours. The money in my pockets turned soft with moisture. So much for the luxury of the coast, which I sighted only through breaks in the forest, glimpses of gorgeous, faraway shores and tiny villages as remote as the Sea of Tranquillity.

Word spread along the road of my slow passage, and children ran from their homes and schools to wave and call. I was cheered, jeered and even horse-whipped by one importunate boy, but always - as had become customary - I was called "sir".

On I climbed, the road narrowing to a pencil line, devoid of almost anything but foot traffic. The landscapes changed - cornfields replacing rice on these drier, steeper slopes - and so did my welcome.

Young children suddenly ran from me, scrambling terrified into the cornfields. Babies wailed and dogs scattered. What sort of strange place was this eastern tip of Bali that dogs ran from cyclists and not after them?

It was as though I was a pioneering tourist on this far-flung nib of land, but I clearly wasn't. In an instant my name changed from "sir" to "pen" and "cigarette" as children and youths shouted their demands for handouts. On uphill stretches of road they ran alongside the bike, keeping pace, yelling, screaming, threatening at times. For two hours I shook my head at almost everybody I passed, my mood becoming as black as the beaches to which I was heading.

At Amed's edge I passed a final group of youths, my head down to avoid contact, but still they turned to stare. "Have a nice trip," one called and waved me on. The words hit me like a cool wind, blowing off my sweat and anger.

In Amed, fishing and tourism appeared to have struck an uneasy balance. Here, as yet, it had been impossible to replace island reality with the sterility of a resort strip. Fishermen's hovels lined the beaches, little more than roofs without walls, their toilets cut into the sand, awaiting the flush of high tide. Fishing boats were stacked so thickly that the beaches beneath might not have existed, and pigs, not touts, sniffed after strangers on the beach.

My flirtation with hills over (for now), I woke to a day of blessed flatness across Bali's north coast. The volcanoes became scenery rather than cruelties, and greetings seemed to ring from every home - "Hello, sir" - and from unseen workers in fields. Even the constant crowing of the fighting cocks caged at the road's edge began to seem like salutations.

People tested the few English phrases they knew - "Thank you, yes"; "I love you"; "How you going, bloke" - and one corn farmer ran from his field, insisting I take his photo.

"One thousand rupiah," he demanded once I'd done so - a 20-cent modelling fee. He asked for my shirt and my watch also but didn't even shrug when I refused. He waved me on with a smile.

And in the spa town of Air Sanih, a new greeting: "You want girl?" I pedalled on, though it had been my intention to stop the night here.

My journey's goal - my pilgrimage, if you like - was only a few kilometres beyond Air Sanih, at the point where the still-unbroken string of villages bunched into the unheralded city of Kubutambahan and the temple regarded by some as the north coast's most impressive, Pura Maduwe Karang. I came not to appreciate its aesthetics; instead, I'd cycled around 300 kilometres to see a single temple carving.

I wandered to the rear of the temple, to the wall on which I knew to be the carving of a cyclist, said to be Dutch artist WOJ Nieuwenkamp. The Balinese I'd spoken to along the north coast simply called him "Captain Nieu", and he was believed to have been the first person to have cycled in Bali, exactly 100 years ago. Somehow he'd finished up immortalised on this temple, the rear wheel of his bike transformed into a frangipani flower.

I sat quietly before the image of my predecessor, thinking not about Nieuwenkamp but about my return to Denpasar. On an island with a spine of volcanoes, there was one way back, and that was up, up and over a choice of caldera rims, but a climb either way of about 1600 metres.

The lactic acid of the previous day still burned at my thighs, and now also at my mind. I'd almost determined to hire a driver to carry me and the bike to the top, but Captain Nieu's stoniness seemed like disapproval. I would decide in the morning.

I continued along the coast to Lovinna, the north coast's answer to Kuta, its off-season beaches all but buried beneath a patina of rubbish. Looking over this littoral tip from the hotel restaurant, I found unintended solace in the words of the resort owner, Gede.

"I've had many cyclists stay here, and those who have climbed the mountain have always stopped here an extra day to rest," Gede had told me, hoping I'd stay longer than my intended night. "Those who have" - three words that filled me with cheer. Other cyclists had made this climb before me.

The main road across the island leaves the north coast at Kubutambahan, looping over the ever-steaming Batur volcano. I returned to Kubutambahan in the early morning, stopping again at Pura Maduwe Karang. Drizzled in holy water by a temple attendant, I sought blessing from Captain Nieu. In the midst of a Hindu full-moon ceremony, I placed the customary frangipani flower behind his ear and willed strength back into my failing legs for this climb into the clouds.

For more than four hours I toiled uphill, the slope wearing but manageable. The road was quiet, with the ubiquitous motorcycles coasting downhill, their engines off to save petrol. The equally ubiquitous dogs watched me pass until, 600 metres up, I was finally attacked, a pair of mutts salivating over my legs. Why now, when I couldn't outride them, when even the grass seemed to move faster than me? This one lot of barking and snarling drew another and suddenly there was a line of aggressive dogs awaiting me through the villages. I almost ran out of drinking water squirting it in their angry, mangy faces.

At the top, smothered in the thickest of fogs, the beauty and the pain of the climb balanced evenly in my mind and legs. The road had been kind, even if its dogs hadn't. In truth, I shouldn't have been surprised by its steady gradient. This island crossing had been built by the colonial Dutch - rely on the Dutch to make even the biggest mountain flat(ter).

The climbing was over, only a relaxed descent to Denpasar to complete my journey. I circuited the caldera rim, which was topped by an unbroken sprawl of villages. Full-moon ceremonies were now in full swing, effigies of gods being carried along the highway, vehicles banking behind them, trapping me in the surreal - a traffic jam atop a volcano.

Finally the road tipped off the rim, carrying me with it, the altitude, fog and rain creating a chill that was almost alpine. Motorcycles rolled carefully through the stream that again flowed over the road but I would not waste this one glorious descent. Freewheeling, I passed the motorcycles, signs flicking by, including the incongruous: "Antiques, Made to Order".

I shivered in the cold and did not care. No rain could stop me now.

skip to main

|

skip to left sidebar

skip to right sidebar

Black as the devil, Hot as hell, Pure as an angel, Sweet as love.

Travel to Indonesia

Contact Our Team:

Raja Kelana Adventures Indonesia

Raja Kelana Adventures Indonesia

Email: putrantos2022@gmail.com

Facebook Messenger: https://www.facebook.com/putranto.sangkoyo