Original Article

October 8, 2010

Celebrating A Gift From Bali: Delicious Confusion

By MATTHEW GUREWITSCH

NO longer quite the inaccessible Shangri-La of antique travelogue, Bali remains, for artists of all kinds and seekers of a spiritual bent, an isle of pristine enchantments. To musicians with or without the cosmic baggage, the fascination lies in the intricately layered pulse and shimmer of the gamelan, the indigenous form of orchestral ensemble, dominated by percussion and associated for centuries with Balinese ritual and devotion.

Since the 1980s the clarinetist and composer Evan Ziporyn has made the pilgrimage often. His new opera, “A House in Bali,” celebrates his forerunner Colin McPhee, a Canadian-born composer and scholar best remembered by fellow acolytes of Bali’s musical heritage. Happening on a few scratchy phonograph records from Bali in 1929, McPhee found his calling. If not for him, the traditions that flourish today might be extinct.

The opera is based mainly on McPhee’s memoirs of the same title, published in 1946 to a rave review in The New York Times by the anthropologist Margaret Mead, who had known McPhee in Bali. “This book,” Mead wrote, “is not only for those who would turn for a few hours from the jangle of modern life to a world where the wheeling pigeons wear bells on their feet and bamboo whistles on the tail feathers, but also for all those who need reassurance that man may again create a world made gracious and habitable by the arts.”

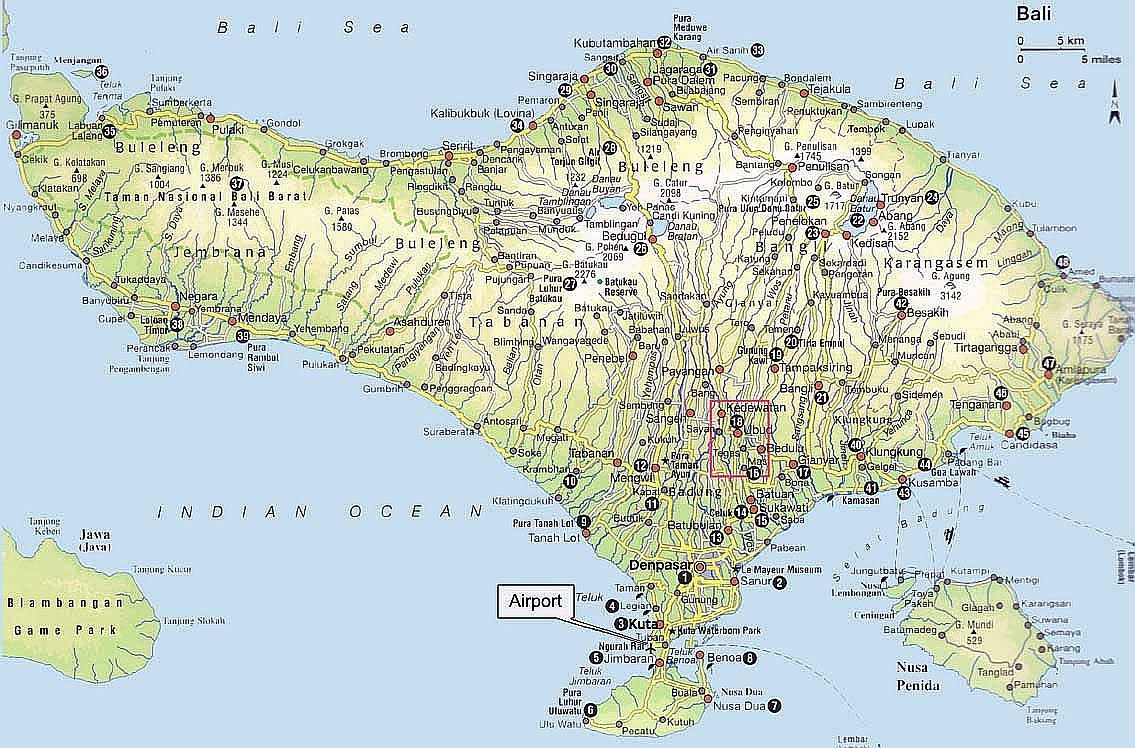

For logistical and sentimental reasons Mr. Ziporyn’s opera received its first, unstaged, preview in June 2009 on the steps of a temple in Ubud, a Balinese arts mecca, surrounded by spreading rice terraces and plunging ravines. The stage premiere followed three months later in Berkeley, Calif. This fall the opera reaches the East Coast, with performances in Boston and in the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival Thursday through Saturday.

The scoring is for a balanced ensemble of Western (the Bang on a Can All-Stars, of which Mr. Ziporyn is a founding member) and performers from Bali whose contributions are equal but for long stretches separate. On Oct. 30 a program of Mr. Ziporyn’s compositions in the Making Music series at Zankel Hall will include further examples of Western-Eastern fusion.

Born in Montreal in 1900, McPhee was hardly the first Western composer to thrill to the gamelan. The former Wagnerian Claude Debussy was transfixed by Balinese musicians at the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1889. The cosmopolitan Maurice Ravel was likewise taken. But it was left to McPhee to sail halfway around the globe to experience the music in its home.

For much of the 1930s he made Bali his home, studying, redeeming historic instruments from pawnbrokers, recruiting children to learn and play. He left in 1938, never to return, but worked on his magnum opus, “Music in Bali,” for the rest of his life. He had barely finished correcting the page proofs in the medical center of the University of California, Los Angeles, when he died, in 1964.

In his memoir McPhee’s evocations of gamelan music are bewitchingly specific.

“At first, as I listened from the house,” one passage begins, “the music was simply a delicious confusion, a strangely sensuous and quite unfathomable art, mysteriously aerial, aeolian, filled with joy and radiance. Each night as the music started up, I experienced the same sensation of freedom and indescribable freshness. There was none of the perfume and sultriness of so much music in the East, for there is nothing purer than the bright, clean sound of metal, cool and ringing and dissolving in the air. Nor was it personal and romantic, in the manner of our own effusive music, but rather, sound broken up into beautiful patterns.”

McPhee went on to analyze the music’s layered architecture: the “slow and chantlike” bass, the “fluid, free” melody in the middle register, the “incessant, shimmering arabesques” high in the treble, which ring, in McPhee’s phrase, “as though beaten out on a thousand little anvils.” Add to all this the punctuation of gongs in many registers, the cat’s-paws and throbbings and thunderclaps of the drums, the tiny crash of doll-size cymbals and the “final glitter” of elfin bells, “contributing shrill overtones that were practically inaudible.”

The scales, though pentatonic, fail to duplicate the assortment we know from the black keys of a piano. And pitch variations from gamelan to gamelan (fundamentally irreconcilable with Western tuning) amount to a science in itself.

The narrative of “A House in Bali” makes delightful reading too, despite some extreme air-brushing. McPhee’s wife, Jane Belo, a woman of means and an anthropologist, is never mentioned, though they traveled (and built the house) on her money. Bowing to the taboos of his time, McPhee passes over the awakening of his homosexuality in Bali, though the charged nature of his attachments to numerous men and boys (consummated or otherwise) is hard to miss. Impending war, one factor that drove him from Bali, is hinted at. Crackdowns by the vice squad, another factor, are not.

In shaping the stage action, the librettist Paul Schick picked out several episodes that McPhee’s readers are sure to remember: the long-drawn-out construction of the house, a comic shakedown by his native neighbors, an unsettling call from a suspected Japanese spy, a visitation by spirits of ill omen. Much of the dialogue is straight from the book; most of the rest quotes writings of the opera’s two other Western characters, Mead and the German artist Walter Spies.

As for the staging, audiences who anticipate an ornamental divertissement along the lines of the “Small House of Uncle Thomas” sequence from “The King and I” are in for a surprise. Mr. Ziporyn seems to have been thinking along these lines too, but the director, Jay Scheib, had other ideas.

“McPhee and Mead and Spies were all deeply involved in image making,” Mr. Scheib said recently between rehearsals on an iffy Skype connection from Ubud. Bali. (Signs of the times: Mr. Ziporyn remembers when the closest telephone was an hour away in the capital, Denpasar.)

“Mead was working out the methodology of visual anthropology, based on the scientific premise that you could infer more about a culture through careful photography rather than through written notes,” Mr. Scheib added. “McPhee shot hours of silent film footage of dance training and rehearsals. And Spies was documenting Balinese culture in a very interesting way through painting.”

With all this in mind Mr. Scheib has opted for extensive use of live video, giving audiences virtual eye contact with performers, even when they are confined to enclosed spaces where viewers in the auditorium cannot actually see them. This, at least, was the case in Berkeley; the production was still evolving.

At the heart of the opera, and often front and center, is Sampih, a shy, skittish country urchin who rescues McPhee from a flash flood, becomes a servant in his household and is trained, at McPhee’s urging, as a dancer. In 1952 the real Sampih achieved international stardom touring coast to coast in the United States as well as performing in London. Back home in Bali two years later, at 28, he was strangled under nebulous circumstances by a killer who was never caught.

Though the correspondences are far from exact, McPhee’s infatuation with Sampih has reminded many of Thomas Mann’s “Death in Venice,” in which the elderly, repressed aesthete Gustav von Aschenbach conceives a fatal attraction for Tadzio, an exotic youth. The opera by Benjamin Britten (a close friend of McPhee’s who for a time shared a Brooklyn brownstone with him and other arty types like Leonard Bernstein) reinforces the parallels, such as they are. Not only did Britten assign the role of Tadzio to a dancer; he also scored his music for gamelan.

The part of McPhee in Mr. Ziporyn’s opera was originally sung by Marc Molomot, who was unavailable for the current performances. His replacement is Peter Tantsits, an adventurous high tenor, who has studied the voluminous source material and McPhee’s circle in depth.

“As an opera singer it’s rare to get to play a character who existed in the flesh, and not all that long ago,” Mr. Tantsits said recently from Boston. “My first impression when I was offered the part was, ‘I’m too young to play Aschenbach,’ which is a role I’d love to do maybe in 20 years. Right now I’m 31, the same age as Colin when he went to Bali. I don’t think the relationship with Sampih was a case of sexual attraction but something more like an adoption. The way he’s described in the book is quite sensual. This is hard to talk about. I don’t think we’ve completely decided what we will decide.”

No Pandora, Mr. Ziporyn has deliberately kept a tight seal on the ambiguities.

“As McPhee presents himself in the book, he’s very transparent yet completely opaque,” Mr. Ziporyn said on a recent visit to New York. “I wanted to mirror that. I think of McPhee almost as a Nabokovian unreliable narrator, as in ‘Pale Fire,’ or even ‘Lolita,’ if that’s not too charged an analogy.

“Every quest is a quest for yourself. In going to Bali, McPhee was looking for his own artistic or personal essence. ‘I’ll always be the outsider,’ he said after he’d been there for years. He was talking about the music, he was talking about Sampih, and he was speaking in general. I wanted to convey that sense and let viewers draw their own conclusions.”

skip to main

|

skip to left sidebar

skip to right sidebar

Black as the devil, Hot as hell, Pure as an angel, Sweet as love.

Travel to Indonesia

Contact Our Team:

Raja Kelana Adventures Indonesia

Raja Kelana Adventures Indonesia

Email: putrantos2022@gmail.com

Facebook Messenger: https://www.facebook.com/putranto.sangkoyo

Our Partner

Blog Archive

-

▼

2010

(19)

-

▼

October

(7)

- Maps of Bali and Bedugul

- Celebrating A Gift From Bali: Delicious Confusion

- Affordable Starbucks brew any time

- A bitter future: People could pay more for coffee

- Indonesia's Sulawesi September coffee exports rise

- Science Matters: Shady practices are good when it ...

- La Nina, Heavy Rains Hurt Production of Commodities

-

▼

October

(7)